After three rounds of failed talks, a trade war between the world’s two largest economies is on.

On Friday, China’s Ministry of Commerce said China will fight back against the US and report to the World Trade Organisation.

“China will not fire its first shot, but is inevitably forced to strike back to defend the core interest of the nation and its people,” a statement from the ministry said. “We will report to the World Trade Organisation on a timely basis.”

The remarks were in response to Washington’s decision to impose 25 per cent duties on a similar amount of Chinese imports, which also came into effect on Friday.

US President Donald Trump had threatened to target another US$400 billion in Chinese products with tariffs if Beijing continued to hit back.

On top of that, each country has prepared a second tariff list of goods worth about US$16 billion. The effective dates are pending as the office of the US trade representative is in the midst of a public comment period on its list.

The trade war became official after Trump repeatedly said he wanted to reverse the United States’ massive trade deficit with China, which rose to about US$375 billion last year. That number is US$100 billion higher than China’s own calculation.

Economists Stephen Gallagher and Yao Wei from Société Générale said a trade war between the US and China would hurt everyone.

“One channel of spillovers is via weakened demand from the two largest economies in the world; and the other equally important and likely quicker transmission would be along global value chains,” they said in a statement.

Time for a reality check for China’s wishful US trade war thinkers

Asia would be worst affected because their economies were deeply embedded in China’s supply chains, the economists said. Taiwan has the highest exposure – 2 per cent of its GDP – to US demand through its value-added contributions to China’s exports, followed by Malaysia, South Korea and Singapore.

Targeted goods:

The American tariffs on a total of US$50 billion worth of Chinese imports were based on a US investigation into China’s forced technology transfers and intellectual property theft from US businesses operating in China. In retaliation, the US government proposed a list of 1,333 targeted products in early April.

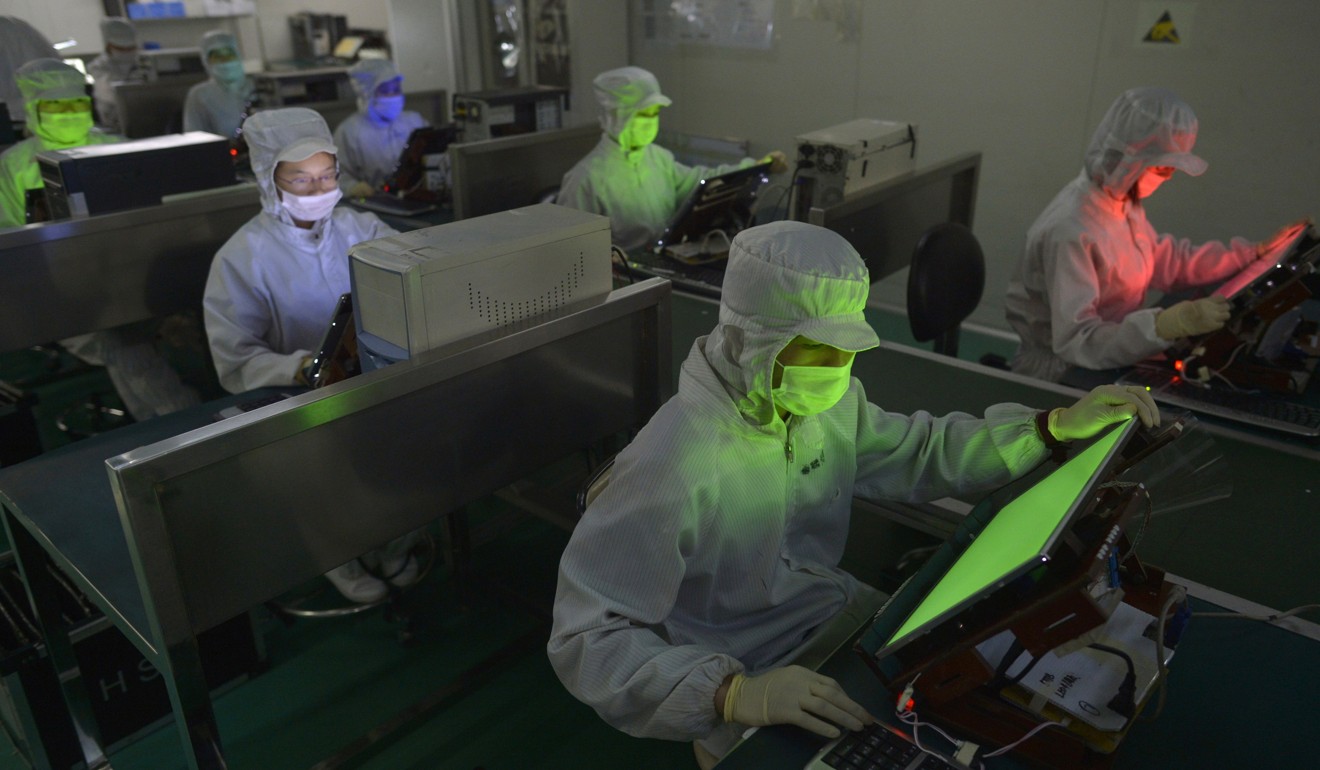

In an updated list published on June 15, Washington dropped many China-made consumer goods, such as TVs and flat panel screens, and added more intermediary products like semiconductors and plastics, after opposition during a public hearing in May.

The second tariff list, which is still under review, focuses particularly on “Made in China 2025”, a Chinese industrial policy aimed at getting ahead in hi-tech industries. It includes electronic integrated circuits and the machines that produce them.

China struck back in April with a list of US$50 billion worth of US imports, many of which were agricultural products. Beijing later removed US$16.3 billion worth of US aircraft from the list and added more food such as fish and nuts.

The primary US goods affected are soybeans and vehicles, while it is mostly Chinese industrial goods hit by US tariffs.

Back in the real world, China-US trade war threats add up to lower growth

Economic costs:

Who bears the brunt of these rounds of tariffs? Eventually consumers.

Analysts said imposing tariffs on Chinese goods such as semiconductors would eventually increase prices for American consumers because they were key components of electronic products. And it’s not an easy business decision for US manufacturers to shift sourcing after tariffs are in place.

“Alternative sources do exist for most of the Chinese products on the targeted list, but less expensive products purchased by less affluent consumers are likely to see larger price hikes as manufacturers substitute more expensive parts for Chinese inputs facing tariffs,” Mary Lovely, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics, wrote.

“These consumers may not see much difference in performance due to one higher-quality part, but they are likely to see a difference at the cash register.”

Chinese consumers, on the other hand, could pay higher prices for imported seafood and fruit.

European businesses in China are ‘hurting’ from Donald Trump’s trade war threats

Future moves:

Beyond the US$50 billion worth of imports, the US also began studying US$200 billion more in Chinese goods for an additional 10 per cent tariff after China retaliated. Trump has also threatened another US$200 billion if China’s countermoves continue.

In theory, China cannot keep matching the scale of the American tariffs. Last year, China imported about US$130 billion worth of goods from the US but exported US$500 billion worth.

So if the trade war keeps escalating, China may have to resort to non-tariff measures, such as limiting US investment in China, although Beijing has so far hesitated to officially go down that route.

One potential target could be the total sales of US-invested companies in China, which reached US$481 billion in 2015, according to data from the US Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis.

“China may well see curbs on US businesses in China as a justifiable response to restrictions on Chinese investment in the US,” Xie Yanmei, an analyst with the investment research firm Gavekal, wrote in a recent note. “There is a large arsenal of regulatory tools it could deploy.”