June shone a little brighter for Donald Trump’s plans to make America great again. After several months of disappointing jobs growth, US hiring picked up steam again. But beneath the surface there’s a problem for the president: the US economy appears to be running out of gas.

On Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics said the US had added 222,000 new jobs in June, comfortably beating expectations. But, once again, most of those jobs were in low-paying industries, and wages are barely keeping pace with inflation. Manufacturing languished while food services and healthcare led the pack.

The numbers were the latest in a strange series of figures coming out about the US that point to an economy that seems almost becalmed, with every positive economic point countered by its opposing force: a strong job market and rising consumer confidence, but lower automotive and retail sales and low overall consumer spending.

The most worrying number for Trump is arguably GDP. The growth in gross domestic product – the broadest measure of US economic health – is sluggish, to say the least. And Trump, whose budget assumes he will double the rate of growth, has gone all out, promising that his business acumen will soon change that.

“I really believe it,” Trump said in an interview with Fox News in April. “We’re saying 3% but I say 4 over the next few years. And I say there’s no reason we shouldn’t be able to get at some point into the future to 5 and above.”

So far, the numbers aren’t supporting him. The US economy grew 1.6% in 2016, its worst performance since 2011, and this year is hardly off to a roaring start. The commerce department released its third – and final – estimate of GDP growth for the first quarter last month, and it came in at a measly 1.4%.

This in an economy where, as the president has been keen to highlight, stock markets are at record highs, there is close to full employment, the oil price remains low and inflation is under control.

Arguably the US is still in Obama’s economy – but that argument won’t hold forever. And while Trump will no doubt continue to blame his predecessor for this era of slow growth, economists are not convinced he can do much to change it.

Gus Faucher, the chief economist at PNC Bank, said the likelihood of returning to the years of 3-4% growth any time soon looks increasingly unlikely. US GDP has not exceeded 3% per annum for a record-breaking 11 years.

“Economic growth under President Trump looks a lot like economic growth under President Obama,” said Faucher.

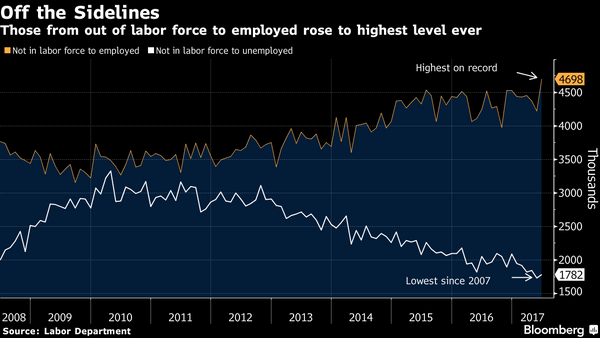

With the unemployment rate at a 16-year low after 81 consecutive months of growth, goosing a little extra gas out of the economy would mean adding more workers. Labor markets have tightened, and Faucher said the data, and his anecdotal experience, suggests employers are struggling to find skilled workers. “There’s a real shortage of people with the right skills out there,” said Faucher. Immigration would be one way around that problem. “But that doesn’t seem very likely,” he said.

Another potential boost for business – Trump’s planned tax reform – is stalled in Congress, and his plans for massive infrastructure spending are also likely to face political headwinds, and in any case could be a mixed blessing. While huge investment in much needed improvements to America’s road, rail and airport network would boost productivity in the long run, in a tight labor market it would pitch business against federally funded projects for skilled workers. “The time to do these kinds of projects is in an era of higher unemployment,” said Faucher.

A recently published report by the Shift commission on the future of work also undermined many of Trump’s claims over employment and a promised 4% GDP growth.

America is getting old and will not have the workforce to support major growth. By 2024, nearly 25% of the workforce is projected to be 55 or older (more than twice the share in 1994). Many of those workers, the Shift commission found, may be staying in the workforce not because they want to, but because they have to. Nearly 30% of respondents 55 and over claimed to have zero retirement savings, and 26% had $50,000 or less.

Numbers are tricky, and the world of work has changed, making it hard for many to see the good news in the jobs report and other economic statistics, said Roy Bahat, head of Bloomberg Beta and co-chair of the Shift Commission. “We have a disconnect between the economic statistics and the facts and feelings about what people are going through,” he said.

For those – like Trump – pinning their hopes on a return to higher growth, there may be even worse news. According to Princeton economist Robert Gordon, there is evidence that the US has taken growth for granted and that a unique, 250-year-old period of growth is over.

In his book The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Gordon argues the kind of rapid economic growth currently considered normal, and expected to continue forever, was in fact a one-time-only event.

Gordon argues the impact of technology can not compare with the impact of the first industrial revolution, which brought steam engines and railroads, and the second, which brought us electricity, the internal combustion engine, running water and indoor toilets, to name a few of its society-shaking changes.

The first two industrial revolutions took about 100 years to filter through society. By contrast, the benefits of the technological/digital age ran out of steam in decades, and have failed to support the sort of growth rates we had come to expect as “normal”.

But, argues Gordon, perhaps higher growth rates never were normal. There was “virtually no economic growth before 1750, suggesting that the rapid progress made over the past 250 years could well be a unique episode in human history rather than a guarantee of endless future advance at the same rate.”

“Yes, we are ‘gigantically’ ahead of where our counterparts were in 1870, but our progress has slowed, and we face stronger barriers to continued growth than were faced by our ancestors a century or two ago,” he writes.