SINCE THE days of Nelson Mandela, one of the most effective slogans of the African National Congress (ANC), South Africa’s ruling party, has been “a better life for all”. The contrast with the old apartheid regime, which promised a good life only for whites, has never needed spelling out. As the party that helped liberate black South Africans from votelessness and segregation, the ANC has ruled uninterrupted since apartheid ended in 1994, always winning national elections by wide margins. The trouble is, when one party has nearly all the power, the kind of people who seek power in order to abuse it and grow rich flock to join that party. Corruption, always a problem, became so widespread under Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s atrocious president from 2009 to 2018, that a more accurate ANC slogan during his rule would have been “a better life for the president and his cronies”.

As our special report in this issue describes, in those nine lost years Mr Zuma’s chums systematically plundered the state. Honest watchdogs were sacked. Investors fled, economic growth stalled, public debt soared and unemployment (even by a narrow definition) rose from 23% to 27%. Eskom, the bloated, looted national electricity firm, can no longer reliably keep the lights on or factories humming. Corruption has crippled public services. Many South Africans are frightened of their own police, and nearly 80% of nine- and ten-year-olds cannot read or understand a simple sentence.

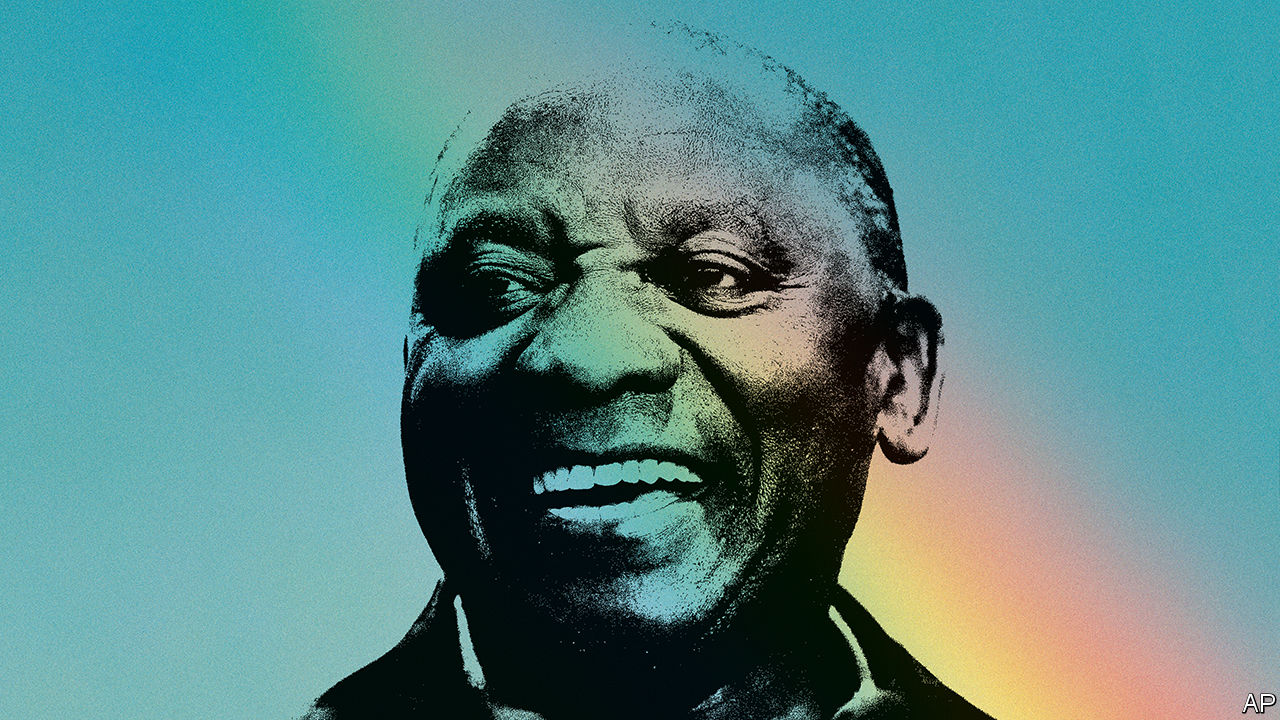

Yet there is hope. Mr Zuma is gone, narrowly ousted by his own party and now charged with some 700 counts of corruption. His replacement as party boss and president of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, is an honest reformer. He is also a tremendously skilful politician—he was one of the chief negotiators who persuaded the apartheid regime to give up power long before it would have been forced to. At elections on May 8th voters have a choice. Do they back the ANC again, trusting that Mr Ramaphosa will continue to clean up the party and revive the nation? Or do they give the opposition a chance? (They cannot vote directly for the president; he is chosen by parliament, in which seats are allocated by proportional representation.)

The case for dumping the ruling party is strong. It has been in power for 25 years—too long for any party, anywhere. Despite Mr Ramaphosa’s efforts, it is still stuffed with crooks, some of them too powerful for the president to sack. Though home to a broad range of ideologies, the ANC has recently seen a worrying resurgence of far-left populism among its cadres. For example, it vows to change the constitution to allow the expropriation of farmland without compensation.

The case for backing the liberal opposition, the Democratic Alliance (DA), is also strong. It is far cleaner than the ANC. Its charismatic young leader, Mmusi Maimane, believes in free markets. The parts of the country that it runs, including Cape Town and Johannesburg, are islands of efficiency in a sea of murk and incompetence. Though the vast majority of municipalities are controlled by the ANC, a recent study by Good Governance Africa, a think-tank, found that 15 of the 20 best-governed were run by the DA, alone or in a coalition. The Economist endorsed the DA in 2014. But this time, with deep reservations, we would cast our notional vote, at the national level, for the ANC.

Our reasons are painfully pragmatic. The DA has the right ideas for fixing South Africa, but is in no position to implement them. It is still seen as the party of those who are white, Indian or Coloured (to use the local term for mixed-race). Because black South Africans are 80% of the population and mostly support the ANC, the DA cannot win (except at the provincial level—and here, we would enthusiastically endorse the DA). For the national parliament, the crucial questions are: will the ANC win an outright majority? And will the election strengthen or weaken Mr Ramaphosa’s reforming hands?

If the ANC does badly, it will undermine Mr Ramaphosa and embolden the large faction within his party that would like to see him stumble. These are the bigwigs who profited from the Zuma years, and did not mind the race-baiting that the Zuma camp used to distract public attention from its own misdeeds. It also includes some of the party’s hard left, who regard Mr Ramaphosa as altogether too friendly to capitalism. Given a chance, Mr Ramaphosa’s ANC rivals would love to replace him with someone more pliable—and that would be disastrous.

If the ANC falls short of a governing majority and has to forge an alliance with a smaller party, things could be even worse. It might climb into bed with the Economic Freedom Fighters, a black-nationalist group that outdoes Mr Zuma in its racist demagoguery and disregard for economic reality. (It wants to seize all white-owned land, and nationalise mines, banks and other “strategic sectors” without compensation, for starters.) Such an alliance would foster an even more bloated, corrupt and ineffective state.

The least bad plausible outcome, then, is for voters to give the ANC a solid majority, thus boosting Mr Ramaphosa and allowing him to shun the populists and face down the mafia within his own party. That way, he can continue the tough work of replacing useless Zuma appointees with law-abiding, competent people. Over the next five years he should also allow prosecutors free rein to hunt looters; break up Eskom’s power monopoly; enact a moratorium on job-killing regulations; take on the teachers’ unions that throttle education reform; and ensure that any land reform extends property rights rather than trampling on them.

The man Madiba wanted

There is a big risk that none of this will happen, that the ANC has grown so rotten that no one can reform it. However, Mr Ramaphosa’s record so far suggests that he is more likely than anyone else to accomplish what is necessary. South Africa cannot afford for him to fail; nor can the rest of Africa. Despite the wasted Zuma years, the rainbow nation still has the continent’s most sophisticated economy, vibrant civil society and feisty media. Having overcome apartheid without a civil war, it has long been an inspiration to the world. All this is now in jeopardy, but Mr Ramaphosa, the man Mandela originally wanted to succeed him, has a chance to save his legacy. He must not blow it.