Hundreds of protesters stormed Hong Kong’s Legislative Council on the 22nd anniversary of the city’s handover to Chinese rule on Monday, breaking glass panels, windows, dismantling furniture, daubing graffiti in the chamber and attempting to put up the British colonial flag.

Brian Leung Kai-ping, 25, was among those who entered the legislature – and the only one who has openly revealed his identity that night.

The storming made international headlines and marked a “quantum leap” for the entire movement against the extradition bill and the city’s push for democracy, he said.

In an exclusive interview with the South China Morning Post, via a Telegram phone call – the social networking tool widely used in the movement – he explained his actions and why he had no regrets.

Where were you on Monday and what was your role?

I skipped another major rally to stay around the Legislative Council complex for nearly eight hours, keeping a close eye on every move. Like most protesters, we had been waiting for this opportunity to make a statement inside Legco. There was of course no clear consensus at the time how long we should occupy it, which underlined the very nature of the extradition bill movement – decentralised, leaderless and spontaneous. We were improvising.

After an hour and a half, reporters observed you removing your mask and asking everyone to stay. Why did you do that?

At the time, more and more people, wary of police countermoves, started to leave the Legco chamber.

I made a risky move to step on the desk of one lawmaker, removed my face mask, and shouted at the top of my voice: “The more people here, the safer we are. Let’s stay and occupy the chamber, we can’t lose no more.”

Some protesters warned me not to remove my mask, but I felt it was the defining moment of the night. I felt we ought to appeal to the crowds to join in and form a barrier and support those inside the Legco complex. No one could tell when we would step foot in Legco again.

As police were drawing closer and closer, after some deliberation, most decided to end the siege. I volunteered to be in front of the camera to read out the key demands of protesters in the chamber.

The last thing I wished to see, after all the action taken, was to have no clear demands put on the table.

If we didn’t do that, the public might only remember the vandalism and point fingers at us as a mob. That would also hand the government a convenient reason to prosecute each and every one of us, which would mark yet another setback to civil society like in the 2014 Occupy movement.

But weren’t the actions of the protesters that day, along with the damage done to Legco, violent?

Be clear that any damage was only done to the Legco building or properties within, not so much to any person or even police officers. Protesters have been restrained in their use of force. They even paid for their drinks in Legco’s canteen.

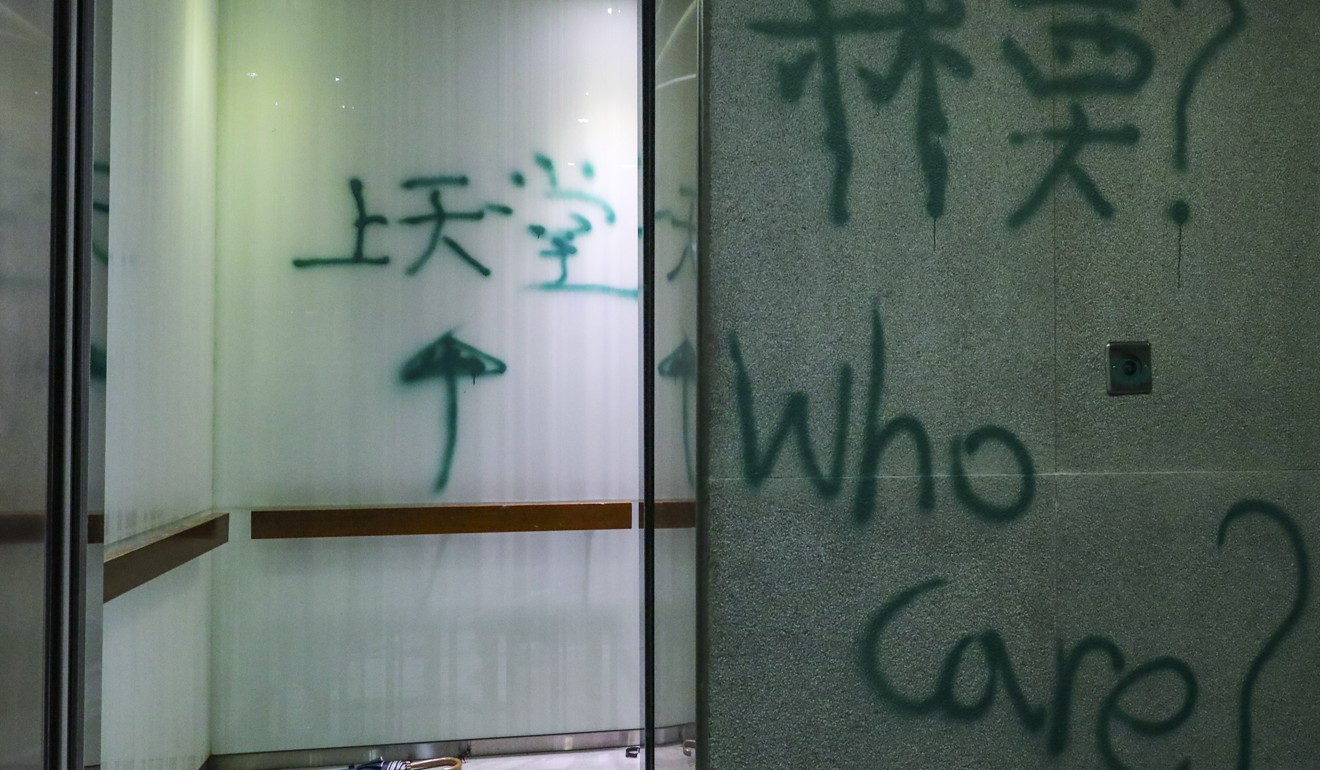

It is worthwhile to note the graffiti was not merely vandalising. For instance, protesters spray-painted and covered up “People’s Republic of China”, leaving behind only “Hong Kong Special Administrative Region”. That is a clear mistrust of the two-systems principle. Most of the other graffiti was about commemorating the three lives lost in this movement.

So they were only telling the public that this was not just mob action but to register the accumulated frustrations of an unfair electoral system. Compared with the death of three people who used their lives to deliver a message, does the damage to several glass frames even count?

It is time to see past the short burst of “violence” committed, and read deeper into what people, particularly the younger generation, are really thinking about.

So what was the young protesters’ state of mind in being part of the July 1 protest and other sieges?

The pursuit of freedom and democracy is what fundamentally drove hundreds of protesters on Monday into Legco, the same goal shared by hundreds of thousands who took to the street earlier. The government has thus far turned a blind eye to our demands, and there was no real change nor real actions tabled. If Carrie Lam claimed herself ready to be more humble, why did she not make clear the suspended bill was completely withdrawn, a move that could easily settle the controversy?

Or, the government could choose not to charge protesters arrested earlier, which we saw happened to those in Taiwan’s Sunflower movement. Or, it could task an independent inquiry into police’s excessive use of force.

Any of these would be welcomed by the civil society, but the government refused to take these calls on board.

At the outset of the protests against this bill, people called for Carrie Lam to step down. But gradually, we came to realise the root of the problem stems from the undemocratic system in selecting the chief executive. Whether Lam remained in office became a secondary issue.

If there was universal suffrage, when 2 million people – almost one-third of the population – took to the streets, any leader would have no choice but to step down.

Also, the government needs to realise that even by improving livelihoods or setting up more consultation platforms to absorb the opposition from our generation, it would do little to help.

You mentioned the three deaths. These are suicide cases. Isn’t it wrong to glamorise them and call them martyrs?

It was evident that protesters were so outraged that three lives were sacrificed throughout this movement, when peaceful means were almost all exhausted. Young protesters were at a point of desperation.

We were not in a position to pass any judgment on their decisions but what the protesters could do was to honour their faith.

One may well argue that time is supposed to be on young people’s side. But with the disqualification and jailing of pro-democracy lawmakers and activists after 2014 “umbrella movement”, the entire generation was banned from the political system. Young people felt burnt out after the defeat of the 2014 movement.

We do not have the luxury of our parents to settle down in another place. Nor do we have the burden of a 30-year mortgage to worry about. Young people have nothing to lose, their only hope is to stay safe to see the sun rise, and hope to join protest another day. We want democracy, now.

Can you share your personal background, your schooling, your parents?

Hong Kong’s social movement has always inspired my academic study. After graduating from the University of Hong Kong with a dual degree in law and politics, I chose for my master’s thesis the topic of how civil society could help democratic transition and prevent authoritarian regimes.

I have always aspired to become a professor and return to teach Hong Kong students to be socially aware in the future.

I really don’t want to mention my family, as I don’t think that’s helpful.

What’s next for the movement? And what’s next for you? And are you in Hong Kong?

Civil society has already exhausted every possible peaceful means, and it is not trying to exercise violence for the sake of violence. The government needs to reflect on its response.

I believe there could be more actions to come, maybe protests. But it’s too early to say.

For my own part, I am not sure whether I can fly to the United States this September to continue my PhD studies in political science at the University of Washington. I am still considering various options, and seeking as much advice as I can.

While I am not yet a political dissident in exile, that is a real threat ahead of me and my peers if the government chooses to press charges against all those who entered Legco, who played their part in this protest.

I am blessed to receive legal advice and other recommendations from my social network, while remaining financially independent through a role as a teaching assistant. For those who may be 17 and 18 years old, there could be real consequences and it is worrying.