The lid is set to be lifted on the less reputable aspects of the history of one of the world’s greatest cities – and, in doing so, extraordinary new light will be shed on a key location involved in the early development of jazz and blues.

Over the last five years, archaeologists have been busy excavating one of history’s most famous red light districts – that of early 20th-century New Orleans. Over the next few years, they aim to analyse up to a million finds unearthed during the dig.

Preliminary examination of the material has so far identified everything from vaginal cleansing nozzles to whiskey bottles, a Colt 45 and other pistols, music-related artefacts and heroin syringes.

New Orleans’ less salubrious history was of course immortalised in one of pop music’s most celebrated songs, “The House of the Rising Sun”, made famous by The Animals back in 1964.

By releasing that record the British pop group unintentionally ensured that the seamier history of one of the world’s greatest cities would never be forgotten.

The Animals’ lyrics warn against drunkenness and gambling and perhaps also against prostitution – but one version of the original lyrics (probably from the 19th century, but first recorded in the 1930s) was arguably much more focused on the third of those activities (but from the prostitute’s perspective, not the john’s).

The different versions of the song certainly resonate with, and appear (to different degrees) to reference, New Orleans’ world-famous “red light” tradition history and the sin-city-related artefacts the archaeologists have been digging up.

Although the original House of the Rising Sun may well have been a 19th-century New Orleans brothel (there are at least three potential candidates there), it is the past half decade’s archaeological investigations that have been shedding extraordinary new light on the classic early 20th-century era of New Orleans’ commercial sex industry when an entire neighbourhood of the city was officially reserved for prostitution.

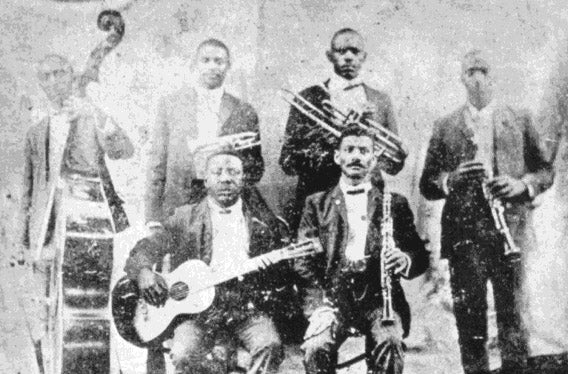

Home to 1,500 working women, dozens of madams, countless bars and gambling dens, and a workplace for hundreds of blues and early jazz musicians, this tiny district and its surrounding areas also ended up making a giant contribution to US and world musical culture. Indeed, some of the most famous early 20th-century popular music musicians played there.

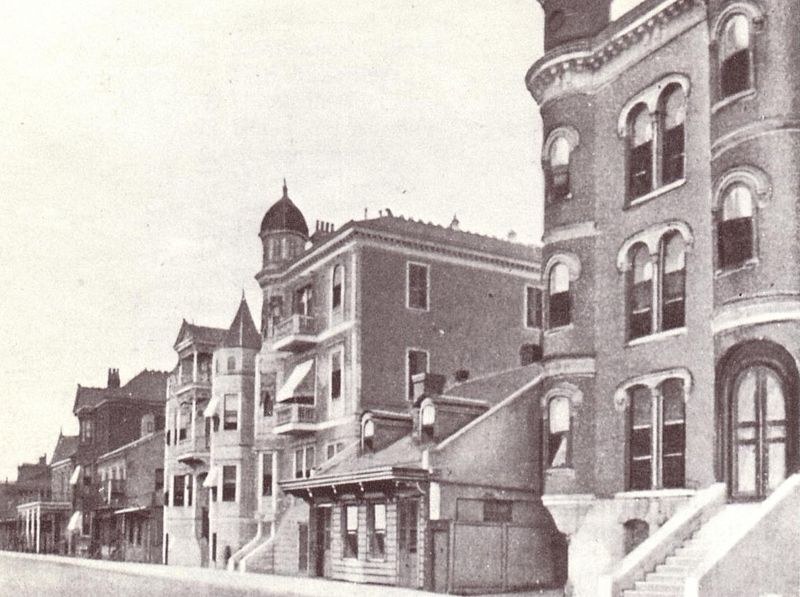

Known as “Storyville”, it was an official prostitution zone, created by municipal lawmakers in 1897 – and closed down in 1917 (because the US military felt it might lead their troops astray – and harm the country’s First World War effort).

Arguably, in just two decades, it had become the most famous red light district on the planet.

The archaeological excavations are now complete – but hundreds of thousands of prostitution, drink, drug, food and music-related finds now await detailed analysis.

Although much of the information about Storyville comes from historical documents (especially a series of annually produced guides to the district’s raunchier services – the famous “Blue Books”), only archaeology can provide some of the missing detail – in particular the relative economic importance of the different activities that flourished there.

Over the past half decade, teams of archaeologists have spent a total of around 25 months systematically investigating Storyville and have unearthed hundreds of thousands of artefacts. The material has already allowed them to get a preliminary enhanced impression of how Storyville’s economy functioned – and more thorough analyses in the future will permit an even greater understanding of the social and cultural ambiance which contributed so much to the early development of popular modern music worldwide.

Prostitution might be the world’s oldest profession, but the dig in New Orleans has been the first time that archaeologists, anywhere in the world, have ever had the opportunity to study a major historic red light district in such detail.

After the red light aspects of Storyville were suppressed in 1917, the area continued as a drinking, gambling and music district for a further 13 years. The whole area was then demolished around 1940 and replaced by a vast housing development (the remnants of the historic old district having been buried beneath it).

It was the demolition of that housing estate in recent years that gave the archaeologists the unique chance to probe one of the world’s most famous and notorious red light districts.

Preliminary analysis of the finds shows that among the artefacts dominating the material culture of Storyville were whiskey bottles (used predominantly by bar and brothel customers) and rouge pots (used by the prostitutes themselves).

Hundreds of each have been unearthed across the site. Not only did the working women have to look good, they also had to smell good – and the archaeological investigation has indeed also yielded dozens of French perfume bottles used by them.

Other finds paint a picture of the women’s lives not provided by any of the historical sources. Venereal disease (VD) was, of course, a constant threat – and the archaeologists have unearthed VD medicine containers, plungers for self-administering medication and special vaginal cleansing nozzles (used to reduce the risk of contracting VD).

Women and men often wore numerous layers of clothing (significantly more than today) – so (in a largely pre-zip era) consummation of a sexual contract often required the undoing of terrifyingly large numbers of buttons. Unsurprisingly, in the urgency of such procedures, a lot broke free of their garments – and archaeologists have now found hundreds of buttons all across Storyville.

The archaeological investigation, led by a senior New Orleans archaeologist – Mike Godzinski of a local cultural resource management company, Earth Search Inc – has also revealed that drugs were relatively important in the economy of the district. Hundreds of cocaine bottles have been unearthed – along with dozens of opium bottles and primitive heroin syringes.

Specialists will also be forensically examining weapons, no doubt used in the district to commit now long-forgotten crimes. Significantly, all the weapons were disposed of down toilets (presumably in an effort to evade police detection). The excavations have yielded three pistols (including a Colt 45 and a Smith and Wesson 38) and six gruesome-looking knives. All nine items were extracted from long-buried Storyville loos.

A different type of potential evidence for violence are human teeth that have been unearthed. It is likely that at least some of their owners were parted from them during drunken brawls (of which there were many).

Mysteriously, the culturally most significant aspect of Storyville (the music) has left remarkably little trace – just one harmonica reed and one accordion key. Musical instruments were of course valuable commodities – and it is likely that the hundreds of blues, ragtime and early jazz musicians who played there took very good care of them – and almost certainly took them home with them, thus leaving very little archaeological trace.

Storyville (named after Alderman Sidney Story, the New Orleans City Council member who oversaw the creation of this epic red light district) was politically, economically, socially and culturally of very substantial historical significance.

It was groundbreakingly liberal, yet in some ways simultaneously shockingly reactionary.

At a time when racial segregation was the legal norm in the southern states, Storyville was an oasis of interracial sexual and cultural exchange. And yet, the interracial aspects (at least in terms of sex) harked back to earlier even more oppressive times when slavery was legal and white plantation owners and masters thought it their God-given right to sexually exploit their female slaves. In Storyville, the customers were exclusively white, while many of the prostitutes were black or mixed race.

Storyville also epitomised the contradiction inherent in prostitution. It could be degrading and (health-wise) dangerous – as evidenced by the VD-related archaeological discoveries – yet it often allowed women from poor backgrounds to enjoy economic independence and increased social mobility. Women working in Storyville were able to earn very substantially greater incomes than other New Orleans women working in other industries. Indeed, for some, it was a way of escaping from the most appalling levels of early 20th-century slum poverty.

Storyville also symbolised another contradiction – between alcoholic prohibition – and drunken liberality. As amply demonstrated by so many of the archaeological finds, New Orleans’ famous red light district was a wet oasis in an otherwise increasingly dry America.

Even after Storyville’s dissolution in 1917 (due to US military disapproval, more on that later), whiskey, wine and every conceivable other alcoholic beverage continued (for just a few more years) to flow freely there. And yet, throughout much of the United States, ever since the 1870s, the Temperance Movement had grown larger and more politically influential.

The introduction, at state level, of local prohibition laws had begun to gather pace in the US by the 1880s. By 1908, parts of New Orleans’ state (Louisiana) had also banned alcohol consumption, as had the whole of neighbouring Mississippi - and yet (protected by New Orleans anti-prohibition municipal government), Storyville (and the rest of the city) stayed as wet and merry as ever.

Indeed, after nationwide alcohol prohibition came into force in 1920, Storyville and the area around it became a place of refuge for people wanting a by-then-illegal drink in an otherwise even drier land. Historical records show that downtown New Orleans (including Storyville itself) was so full of liquor during nationwide prohibition that it attracted an absolutely vast number of police prohibition enforcement raids (683 in total).

The collision between wider societal morality and a desire for sexual freedom expressed itself in another collision between Storyville and the wider American world. Relatively open sexual freedom had long been a feature of American culture (partly courtesy of the eastern urban expansion and the western “Wild West” ethos and the 1860s Civil War) – but by the fourth quarter of the 19th century, a massive reaction had set in, and from 1873 onwards, contraception was being increasingly discouraged. To some extent, Storyville had to function within that increasingly contradictory environment.

After 1897, local municipal law and commercial interests actively encouraged prostitution there, while very illiberal federal laws (and in many areas of the country, state laws) actively sought to prevent prostitutes gaining access to contraceptive information and devices. This moral illiberality had been initially triggered by the Civil War, which had created a veritable epidemic of pornography and venereal disease (including a massively increased incidence of syphilis).

The Storyville archaeological investigation has now, for the first time, provided historians with artefactual evidence of the sheer scale of the sex industry there.

Last, but not least, this moral contradiction came to a head between New Orleans’ liberal instincts and the US military’s decidedly less liberal ones. For, in 1917, Storyville’s brothels were forced to close as a result of intense political pressure exerted by the US military – especially the Navy.

New Orleans was a major US Navy port – and naval chiefs were nervous that American sailors might be “distracted” by the fleshpots of Storyville – and that many might contract syphilis and other venereal diseases, which would potentially undermine the US war effort (1917 was, after all, the year that America joined the Allies in World War One). Indeed, throughout the US, any concentrated prostitution activity located within five miles of any military installation was outlawed.

Storyville only existed as a red light district for two decades (1897-1917) – but, in those 20 years, it played a major role in the history of popular culture.

Blues and early forms of jazz were crucial aspects of the district (as evidenced by the discovery, by archaeologists, of rare fragments of musical instruments there) – and of course, both musical genres subsequently fed into and helped create modern rock, while blues fed into R&B – and jazz eventually even influenced modern hip hop.

Although blues and early jazz weren’t born in Storyville, it was partly there and in the surrounding neighbourhoods that they reached the critical mass, in terms of breakout popularity, that helped enable them to become the giant cultural phenomena and influences that they subsequently became.

Storyville was not just a historically important sex and entertainment hub, but was also an economic powerhouse contributing vastly to New Orleans’ economy. Even more crucially, that economic status made it possible for much larger numbers of blues and early jazz musicians to flourish financially there and nearby than would otherwise have been the case.

Indeed, it is arguable that, without the bars, clubs and brothels of downtown New Orleans (including and perhaps especially Storyville), blues and early jazz might never have had the economic base, which allowed them to so spectacularly cross over into the mainstream.

Playing in Storyville were some of the most gifted early 20th-century musicians.

The famous early jazz star King Joe Oliver – the mentor and teacher of Louis Armstrong – often played cornet in Storyville. A band which he co-led was considered the best in New Orleans.

King Oliver’s colleague Kid Ory (the other co-leader of that band) was one of America’s greatest trombonists.

Manuel Perez, another famous cornet player who helped develop ragtime and early jazz, also regularly played in Storyville.

Sidney Bechet, a brilliant clarinettist and composer, played as a teenager at one of the red light district’s most famous venues, Pete Lala’s Jazz Club.

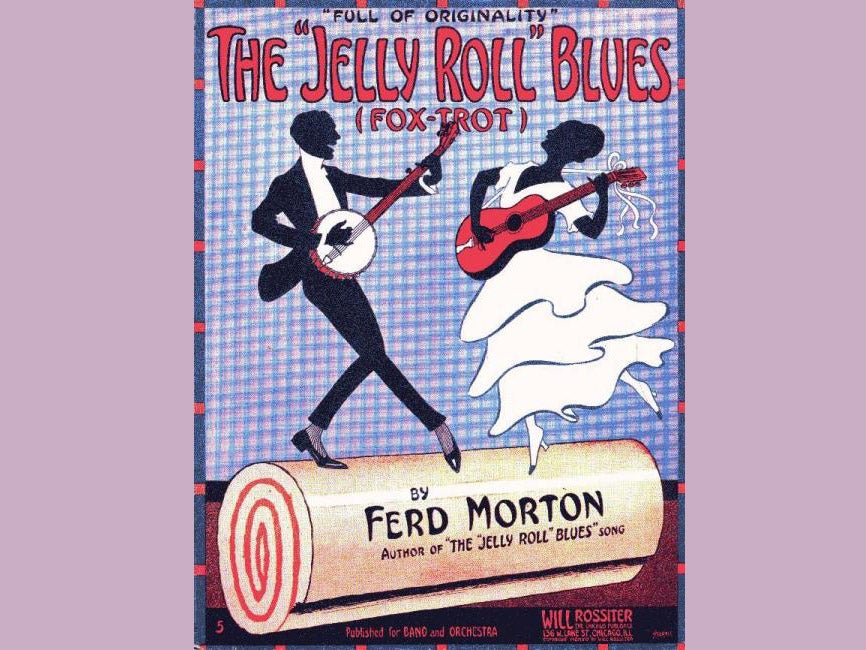

For some musicians, playing in Storyville, though lucrative, could have at least temporarily bad consequences. Jelly Roll Morton, who composed jazz’s first ever published composition, “Jelly Roll Blues”, was kicked out of his home (probably in his mid teens) when his apparently church-going great grandfather discovered he was playing the piano and singing in a Storyville brothel.

Even as a teenager, the lyrics he composed and sang were decidedly risque – and his professional nickname, “Jelly Roll”, was awarded to him to celebrate the lively subject matter of his compositions (“jelly roll” was African American slang for female genitalia).

However, the remarkable history of Storyville isn’t just a tale of sex, drugs and popular music.

It was above all an extraordinary honeypot that could make men (and some women) extremely rich.

The whole city had a political and economic stake in its existence and its financial success.

As demonstrated by the archaeological investigation, vast quantities of drink were consumed in and around the district – so the alcoholic beverage merchants made a fortune from it (New Orleans was one of America’s major alcohol importation ports).

The landlords enjoyed even bigger profit enhancements. When the city fathers passed local legislation to create Storyville in 1897, rents in the district rose by up to 1,500 per cent overnight. Many of the buildings which became brothels and bars and gambling joints were owned by respectable civic and business leaders – and even by the church.

The police (or at least some of them) also made a killing – by operating protection rackets (local brothels and other businesses had to pay police syndicates for the privilege of not being hassled and arrested for a bewilderingly wide range of potential misdemeanours).

But the archaeological investigation is revealing that the Storyville’s gangsters still had to hurriedly dispose of incriminating weapons – usually by throwing them down the district’s loos.

The tourism industry also loved Storyville. The place had been conjured into existence at the very time that New Orleans was redoubling its efforts to attract visitors from all over the country (especially businessmen attending important conventions which New Orleans constantly sought to attract and host).

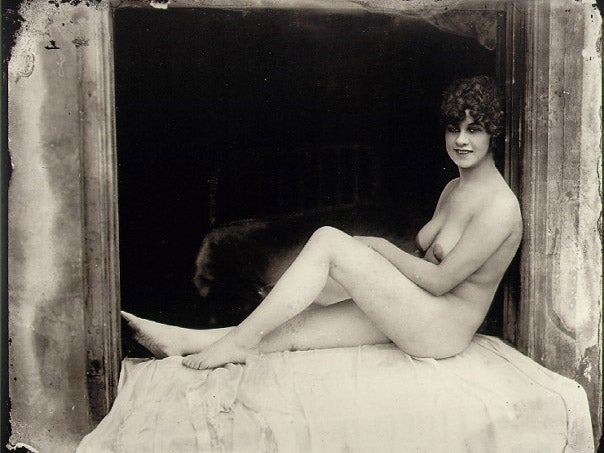

Indeed, tourists and businessmen arriving by train in New Orleans were often (and somewhat controversially) treated to a free preview of Storyville – for the district’s prostitutes would stand naked on their balconies and wave at the passing rail passengers. Certainly, the area was the best marketed red light district in America and probably the world.

In modern New Orleans, the job of fully analysing and properly recording the often poignant detritus of Storyville’s remarkable social history, unearthed by the archaeologists, still lies ahead.

Virtually the only other remnants of the district are the famous and intriguingly illustrated “Blue Book” brothel guides and other documents – and a remarkable collection of photographs of Storyville’s prostitutes and madams.

But at present nobody knows whether the thousands of archaeological finds, the surviving documents and the old and extraordinarily evocative black-and-white photos will ever be brought together to permanently commemorate the pain, the vibrancy, the achievements and the cultural legacy of this tiny, fascinating patch of historic America. Indeed, in that sense, the final chapter of the story of the House of the Rising Sun has yet to be told.