Ciera Jackson filed for a restraining order, claiming in court documents that her ex-boyfriend, Victor Whittier, had sent a series of threatening text messages and then lurked outside her home. Jackson, 24, had previously called police when Whittier broke into her apartment and ransacked it, but she chose not to pursue criminal charges, according to authorities.

She had asked her property manager whether she could break her lease, hoping to secretly – and safely – escape with her 11-year-old brother, whom she was raising.

“I have been physically abused by the respondent before,” Jackson wrote in court papers, adding that she knew “what he is capable of doing”.

In August 2017, a judge granted Jackson a year-long restraining order against Whittier; he was to have no contact with her and stay at least 2,500ft away.

Eleven days later, Jackson was dead.

Authorities say Whittier shot Jackson four times through her apartment window, the restraining order lying on a microwave just a few feet from her body. When investigators asked whether Jackson had trouble with anyone, her brother handed them the document.

Jackson’s death came with clear warning signs. It was a murder that played out in slow motion as all of her efforts, and those of law enforcement and the courts, failed to stop what she saw as inevitable. A Washington Post analysis of 4,484 killings of women in 47 major US cities over the last decade found that nearly half of those who were murdered – 46 per cent – died at the hands of an intimate partner.

In a close analysis of homicides in five of the cities, analysts found that more than a third of all men who killed a current or former intimate partner had been publicly known to be a potential threat to their loved one.

In Fort Worth, Las Vegas, Oklahoma City, San Diego and St Louis, 36 per cent of the 280 men implicated in a domestic killing had a previous restraining order against them or had been convicted of domestic abuse or a violent crime, including murder.

Killings of intimate partners often are especially brutal, involving close encounters such as stabbings, strangulation and beatings, the analysis found.

Nearly a quarter of the 2,051 women killed by intimate partners were stabbed, compared with fewer than 10 per cent of all other homicides. Eighteen per cent of women who were killed by partners were attacked with a blunt object or no weapon, compared with 8 per cent of other homicide victims. While a gun was used in 80 per cent of all other murders, just over half of all women killed as a result of domestic violence were attacked with a gun.

Violent choking is almost entirely confined to fatal domestic attacks on women – while fewer than 1 per cent of all homicides result from strangulation, 6 per cent of women killed by intimate partners die in this manner. It’s also a warning sign. Those who attempt to strangle an intimate partner are far more likely to later commit extreme acts of violence, police and researchers say, and many in law enforcement believe it to be a strong indicator that an abusive relationship could turn fatal.

The Post’s analysis comes as part of a year-long effort to examine homicide in major American cities and the extent to which authorities – at a time when the national murder rate nears historic lows – fail to solve killings. Unlike other types of homicide, domestic killings often involve killers who leave a long trail of warning signs or signal their intent, in some cases threatening to kill their victims.

Domestic violence cases are complex, often involving victims who are reluctant to report abuse for fear of further angering their abusers or losing their financial support. Those who do seek help often encounter fractured legal networks and a lack of cohesive support. Many victims are killed even after police and courts have stepped in.

The analysis of domestic killings draws on public records and news reports, and it probably understates how often American women are killed by boyfriends, husbands and ex-partners because some cities offer scant information about their homicide cases. The tally counts murder-suicides, which some prosecutors’ offices do not have in their data sets because, with the killers dead, there are no criminal cases to pursue.

The data aligns with recent research into the murders of women, including a report from Northeastern University criminology professor James Alan Fox, who used FBI data from police departments to find that 44.8 per cent of women killed from 2007 to 2016 were murdered by an intimate partner. Fox also found that 5 per cent of all men killed from 2007 to 2016 were murdered by an intimate partner.

Fox says it is difficult to determine what actions might lead from abuse to fatal violence, noting that many people exhibit behaviour that might be a red flag for a potentially deadly attack but never go on to kill.

“There are numerous motives for intimate-partner homicide,” Fox says. “Previous acts of violence ... a separation or divorce – these are all precursors, but they’re not reliably predictive. And that’s the struggle.”

Authorities – and those who work with victims of intimate-partner violence – say the most glaring signs that a relationship could turn fatal are often elusive to law enforcement, including things that are obvious to those around them but rarely make the public record: death threats behind closed doors, easy access to guns, jealousy, separation or a breakup.

“We have a lot of repeat victims and repeat offenders because, for example, it may be the victim’s only source of a babysitter,” says lieutenant Amy Parker-Stayton, commander of the family violence and sex crimes unit in the St Louis Metropolitan Police Department. “It may be the victim’s only source of income. The victim comes back and says, ‘I love him; I don’t want to prosecute,’ and unfortunately, if it happens again, we revisit it again. And it may be too late. On the second or the third time, they may be dead.”

Tracy Prior, chief deputy district attorney in San Diego County, says about 40 per cent of the defendants in the domestic homicide cases that her office prosecuted from 2007 to 2017 had a prior criminal record.

“You wish you had a crystal ball, because no prosecutor wants to see the same perpetrator doing that again,” Prior says.

But the most basic step authorities instruct abused women to take – filing a restraining order – can lead to fatal violence because involving the legal system often is a flash point. One prosecutor tells women who request an order to do so with a backpack and a plan.

“It’s not a bulletproof vest – he can still come after you,” says Karen Parker, president and CEO of Safe Alliance, which helps abused women in Charlotte, North Carolina. Some 60 of 119 women killed in the city from 2007 to 2017 were murdered by an intimate partner.

And legally, there is not much that can happen until an order is violated.

“That’s what people think they are supposed to do when they feel as though they are threatened or they are in danger. We tell them, ‘Get an order of protection’,” says Travis Partney, chief trial attorney in the St Louis circuit attorney’s office, which prosecuted Whittier.

“And she did,” he says of Jackson. “And she’s dead.”

* * *

Domestic murders often occur after there have been many chances to intervene and abuse and violence have escalated. The abused – the one who must initiate a cry for help – often doesn’t want to participate in a legal process that will harm the abuser.

Art Clayton, chief of the Intimate Partner Violence Unit in the district attorney’s office in Tarrant County, Texas, says law enforcement officials struggle with repetitive abuse cases because some victims are reluctant to help, even as violence against them increases.

“Most domestic violence victims are not cooperative,” Clayton says.

Minerva Cisneros of Tarrant County’s Fort Worth believed her abusive situation would change and didn’t want to cooperate with police and prosecutors because she thought it could hurt her partner and cause her to lose custody of her children.

Cisneros arrived at a hospital in August 2014 with a bloody nose, busted lip, strangulation marks on her neck and blood in her eyes, authorities said. Her common-law husband, Arturo Sigala, allegedly tried to strangle her until she lost consciousness. She was eight months pregnant with their third child.

The hospital contacted authorities, but the case – one among hundreds of others at the time – stalled because the police detective assigned to it could not reach Cisneros, who was not cooperating with the investigation, according to Fort Worth police.

As the criminal case waited, records show that child protective services officials opened a separate inquiry into Cisneros, alleging that she had failed to protect her children from witnessing the abuse she suffered. She and Sigala were required to enter couples counselling, and she took a class on how to manage her husband’s violent behaviour, according to Allenna Bangs, a Tarrant County prosecutor. Family members and authorities said Cisneros became concerned that she could lose custody. Child protective services officials did not respond to a request for comment.

About six months after Cisneros was hospitalised, the assault allegations against Sigala were reassigned to another Fort Worth detective. The officer spoke with Cisneros about her abuse and also spoke to Sigala, who confirmed that he had hit his wife multiple times but denied that he had strangled her into unconsciousness. He told police he had been drunk at the time.

Authorities acquired an arrest warrant almost immediately, and Sigala was taken into custody days later, police said. Cisneros then visited the Tarrant County district attorney’s office and said she was adamant that she was safe. She wanted her husband back home and the criminal case against him dismissed.

A grand jury listened: it did not indict him.

In the early hours of Christmas Day 2015 – just more than a year after the attempted strangulation – Sigala called 911: “Something happened; my wife needs help,” he told the operator. “I sat down and the gun went off.”

Sigala, who had been in the country illegally, jumped in the couple’s car and fled to Mexico. Shortly after, police arrived at the couple’s home, which was decorated for Christmas and smelled of the brisket and pozole, a Mexican stew, that Cisneros had cooked hours earlier.

Cisneros and her 15-month-old daughter, Alyson, were lying side by side in bed. Cisneros was dead, shot once in the chest. Alyson was alive, her hair caked with her mother’s blood. The shell casing and the gun were missing.

Sigala was later arrested at the US border and put on trial, where he was convicted of murder and sentenced to 50 years in prison.

The couple’s children are now seven, six, and four – and are in the care of Cisneros’ family.

Sigala’s lawyer, Richard Henderson, said his client’s case “looked more like an accidental shooting” than a murder. “To me, the facts didn’t fit classic domestic violence,” he said.

Sigala has appealed his case; his appellate lawyer declined to comment.

Authorities see the case, in hindsight, as having been avoidable, one that was complicated by a fraught relationship, a mother concerned about losing her children and lack of a cooperating witness.

“I reflect upon all of the missteps made across all of the agencies involved in Minerva Cisneros’ cases and realise that her murder was potentially preventable,” Bangs said. “We know that we cannot help or prevent violence against people we don’t know about. Minerva was not one of those people.”

* * *

Attempted strangulation, as was seen in Cisneros’ case, has rapidly gained attention as a strong indicator that an abusive relationship could turn fatal.

Researchers, including Jacquelyn Campbell, a nurse and professor at Johns Hopkins University, have found that a woman is far more likely to be killed by an intimate partner who has attempted to strangle her in the past. Campbell said many women don’t know that medical authorities and police consider the act especially violent and a potential precursor to murder.

“Strangulation is the one common factor that emerges so very, very often,” says sergeant Craig Varnum, supervisor of the domestic violence unit at the Charlotte-Mecklenburg police department. The department has trained all of its members – as well as prosecutors, judges and health-care providers – to spot the signs of strangulation, which include bloodshot eyes, sore throat and confusion. Varnum says the department’s next goal is to create a task force to identify, prosecute and track men who strangle women.

Attempted strangulation is “the edge of homicide,” says Casey Gwinn, a former San Diego city attorney and president and co-founder of Alliance for Hope, which works with domestic violence and sexual assault victims. His organisation trains first responders and doctors to spot the signs so they can intervene.

“Our goal is to say as soon as you hear ‘he choked me’, bells and whistles will be going off,” Gwinn says.

Benjamin, of the Fort Worth police force, says men who try to strangle have been linked to extreme violence, including against police officers.

“In my opinion, any man who becomes so angry at a loved one that he can strangle them ... is a man who is predisposed to murder,” Benjamin says.

Suzanne Parsons, a Fort Worth real estate agent, long feared that her husband, John St Angelo, would kill her. The couple married in their 40s but had known each other since childhood, and Parsons endured relentless violence during their three-year marriage. St Angelo refused to let her leave the house, dragged her from the shower by the hair, assaulted her because her cellphone was locked and tried to strangle her while they were on holiday in Mexico, according to her son, Joel Bishop.

St Angelo, once an affluent developer, depleted his savings. The couple defaulted on their mortgage, and St Angelo started using drugs and gambling, says Bangs, the prosecutor.

When St Angelo moved out in May 2013, Parsons served him with divorce papers, requested a temporary restraining order, bought a gun and applied for a concealed handgun licence, Bangs says.

In December 2013, Parsons called the police to report that someone had set her swimming pool equipment on fire. Prosecutors said Parsons was confident that St Angelo was the perpetrator, but police did not have enough evidence to charge him.

Days later, Fort Worth police found Parsons’ body slumped on her office floor at work. Her hands were covered in blood and defensive wounds. Half of a red-polished fingernail was ripped off and was lying on the carpet nearby, beside a blood-smeared necklace of interlocking hearts. Prosecutors said St Angelo stabbed Parsons about two dozen times.

He was arrested the following day after attempting suicide and was later convicted of murder, receiving a life sentence. His lawyer, Kathy Lowthorp, said in an interview that Parsons was the aggressor in the violent encounter and that St Angelo stabbed her in self-defence.

* * *

One of the biggest obstacles to preventing domestic violence homicide is the fractured system that aims to deal with domestic strife. In some cities, women often have to navigate multiple offices, disparate bureaucracies and opaque processes to seek help.

When Kimberly Garrett began working as the victims services coordinator for the Oklahoma City police department in 2011, she was shocked by what she found. The onus was on victims to figure out where they needed to go for help, and women often had to drive all over the city – to a courthouse one day, a police station the next, a social worker a week later. Some women would just give up, Garrett says.

According to analysis, 47 of 104 women killed over the last decade in Oklahoma City were murdered by an intimate partner.

Garrett began work to open Palomar, a one-stop resource for victims of domestic violence and sexual abuse known as a family justice centre, in February 2017. People began asking for help filing restraining orders, seeking criminal charges and finding social services before the building opened.

There are 130 family justice centres nationwide, according to the Alliance for Hope, and others in at least 20 countries.

Many offer counselling and child care and allow domestic violence victims to attend court via video monitor so they do not have to be in the same room as their abusers, a shift that makes victims feel safer.

“There are people who have been in the field for a long time, and they’re comfortable with the status quo, and they feel like agencies should be isolated,” Garrett says. “I think, at the end of the day, that’s made it really hard for victims. There’s unintentional consequences.”

Advocates also battle the perception that domestic violence is shameful and should remain a private family matter.

“Twenty years ago or 30 years ago, it was a hidden secret, and now we’re finding that it’s still difficult to talk about,” says Ruth Glenn, president and CEO of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. “We don’t want to talk about it until there’s an event.”

As a result of Cisneros’ killing and other similar cases in Fort Worth, Tarrant County district attorney Sharen Wilson dramatically changed how the office handles domestic cases, putting the Texas county at the vanguard of prevention.

She created a specialised domestic violence division, which handles the office’s most serious offences. It has 450 to 600 cases at any given time

Wilson’s office stopped accepting requests from women to drop charges against their suspected abusers. It now brings forward cases even if a woman doesn’t want to cooperate, evaluating the strength or weakness of a case through evidence such as medical records, photographs taken by forensic investigators and 911 calls. The approach, known as evidence-based prosecution, is increasingly in the US.

“There are some people who, quite frankly, just aren’t ready, but if we can piece together a case in her absence or piece together a case even without her wanting us to, that’s our responsibility to protect her and the community and the family,” says Spencer B Merriweather III, the district attorney in Mecklenburg County.

In February 2017, six Texas counties, including Tarrant, received pilot funding to form domestic violence teams to intervene in cases such as Cisneros’. Law enforcement officials and victim support organisations meet monthly to discuss cases. District judge Mollee Westfall built a docket entirely of high-risk cases, and domestic violence killings in Tarrant County have fallen since the changes were implemented.

“We’re trying to keep people alive,” Westfall says. “It’s very disturbing to watch case after case unfold and know there were a bunch of warning signs that are easy to read.”

Police departments across the country use a lethality assessment to gauge the danger that a woman in an abusive relationship faces. They connect victims who are at high risk to advocates.

The assessments consist of questions including whether an abuser owns or has access to a gun, whether the victim moved out in the last year or whether a death threat was made, says Campbell, of Johns Hopkins, who developed the assessments.

“If she’s at high danger and high risk and she’s told, ‘You are at high risk,’ that being told is an important part of the process,” Campbell says. “Women will oftentimes underestimate their risk of being killed.”

By the time Desirae Parnell began making a move to protect herself, she was already facing extreme danger.

In December 2016, Parnell contemplated filing a restraining order against Zachary Blake, the father of her two children, according to her mother, Carolyn. Desirae met Blake in 2007 and fell for him quickly. She gave birth to a son in 2009, and Blake wanted her to stop working, her mother says.

“It was his way of controlling,” Carolyn Parnell says. “He took everything. Her self-esteem, everything, away from her.”

Parnell gave birth to a second son in 2011 and, against Blake’s wishes, got a job at an urgent-care clinic in Oklahoma City. Parnell thrived, eventually managing two clinics. But her relationship deteriorated, and emotional abuse began to escalate to physical attacks, her mother says. In 2016, Parnell found Blake using heroin in the couple’s bathroom and left him, her mother says. He sent threatening text messages that she reported to police, but her mother says the threats didn’t rise to the level of a crime.

Parnell started putting her life back together. She coached her sons’ baseball team. And she tried to keep Blake involved with the boys. One night, she asked Blake to take their sons to a wrestling event. He took them to a friend’s apartment instead, and Carolyn Parnell says her daughter realised she no longer trusted Blake and wanted to put legal distance between them, so she told him she wanted to file a restraining order, also known as a victim protective order, or VPO.

“He told her, ‘If you get a VPO, I will kill you, and I will kill myself’,” Carolyn Parnell says. “We just thought he was blowing air, like he always did.”

Though she knew little about the process, Desirae Parnell decided that week to seek a protective order with the help of a friend who was a police officer, her mother says.

Desirae was later seen getting into her car outside one of her clinics, and Blake was hiding inside, Carolyn Parnell says. Parnell drove around a car park before getting out. Blake remained inside, aimed a gun out of the driver’s side window and shot her in the head, killing her instantly. He then killed himself, according to Oklahoma City police.

Desirae Parnell died in December 2016. The public viewing of her body was three days later, on what would have been her 31st birthday. Her parents decided to have a closed casket.

Carolyn Parnell and her husband are now raising the couple’s sons, who are nine and seven. They are doing well despite the trauma, she says. When she told them that both of their parents were dead, the older boy knew almost instinctively that their father hurt their mother: “The oldest one looked up and said, ‘Daddy shot Mama, didn’t he?’ And I said, ‘Yes, baby, he did.’ ”

* * *

Last year, San Diego was the nation’s safest of America’s largest cities in terms of violent crime, according to the FBI. But it has a long-standing problem with domestic homicides. Analysis shows that 51 per cent of women killed in the city during the past decade were murdered by an intimate partner, the highest of any city in the latest research.

While some jurisdictions are focusing on the precursors to homicide, San Diego County has made headway in its focus on domestic violence by also carefully examining the killings afterwards. Each time a person in the county is killed by an intimate partner, representatives from law enforcement, social services, the medical field, schools and the military gather and try to determine where things went awry. The group is known as the fatality review team.

The district attorney’s family protection unit, which covers sprawling San Diego County, says it prosecuted 94 domestic violence homicides from 2007 to 2017, though the number of domestic violence deaths in the county has dropped in the last few years.

“All egos have to be checked at the door, and we’re going to look together as a community and ask: Can we prevent that murder?” says Prior, the chief deputy district attorney.

Did the killer have access to weapons? Was there a previous escalation of domestic violence, and, if so, was it reported? Was there a history of threats? Did the family have contact with child welfare agencies? Did the victim take out a restraining order?

The nation’s first family justice centre opened in San Diego in 2002, and the fatality review team started 22 years ago. Its police department has a dedicated domestic violence unit. It was on the leading edge of programmes that are now commonplace around the country, including strangulation training. The San Diego County district attorney’s office received a grant last year to create an algorithm to predict which cases have the potential to turn fatal.

* * *

In Missouri, officials are just beginning to dig deep into domestic violence, and they are battling a pervasive problem that exists with all types of crimes: getting victims and witnesses to cooperate.

St Louis circuit attorney Kimberly M Gardner is lobbying to change state laws that require victims to turn over a trove of personal information, including their last known address, when they seek a restraining order.

“Our laws are very lax in how we protect victims and witnesses,” she says.

The state created a domestic violence fatality review team for St Louis last month, and the city started using the lethality assessment earlier this year.

In St Louis, 48 of 148 women killed from 2007 to 2017 were murdered by an intimate partner, research found.

In the case of Ciera Jackson, there were eight possible witnesses outside her apartment building, but prosecutors used only one, her neighbour, to cooperate and testify at Whittier’s trial.

The other witness was Jackson’s brother, Reggie, who was 11 at the time of the murder. He was playing video games in the apartment when the gunshots were fired. Normally, if there were gunshots in the area, Ciera would tell Reggie to get down, but he did not hear her. He said he later found his sister’s body.

A jury found Whittier guilty of first-degree murder and armed criminal action. His public defender, Erika Wurst, declined to comment on the case.

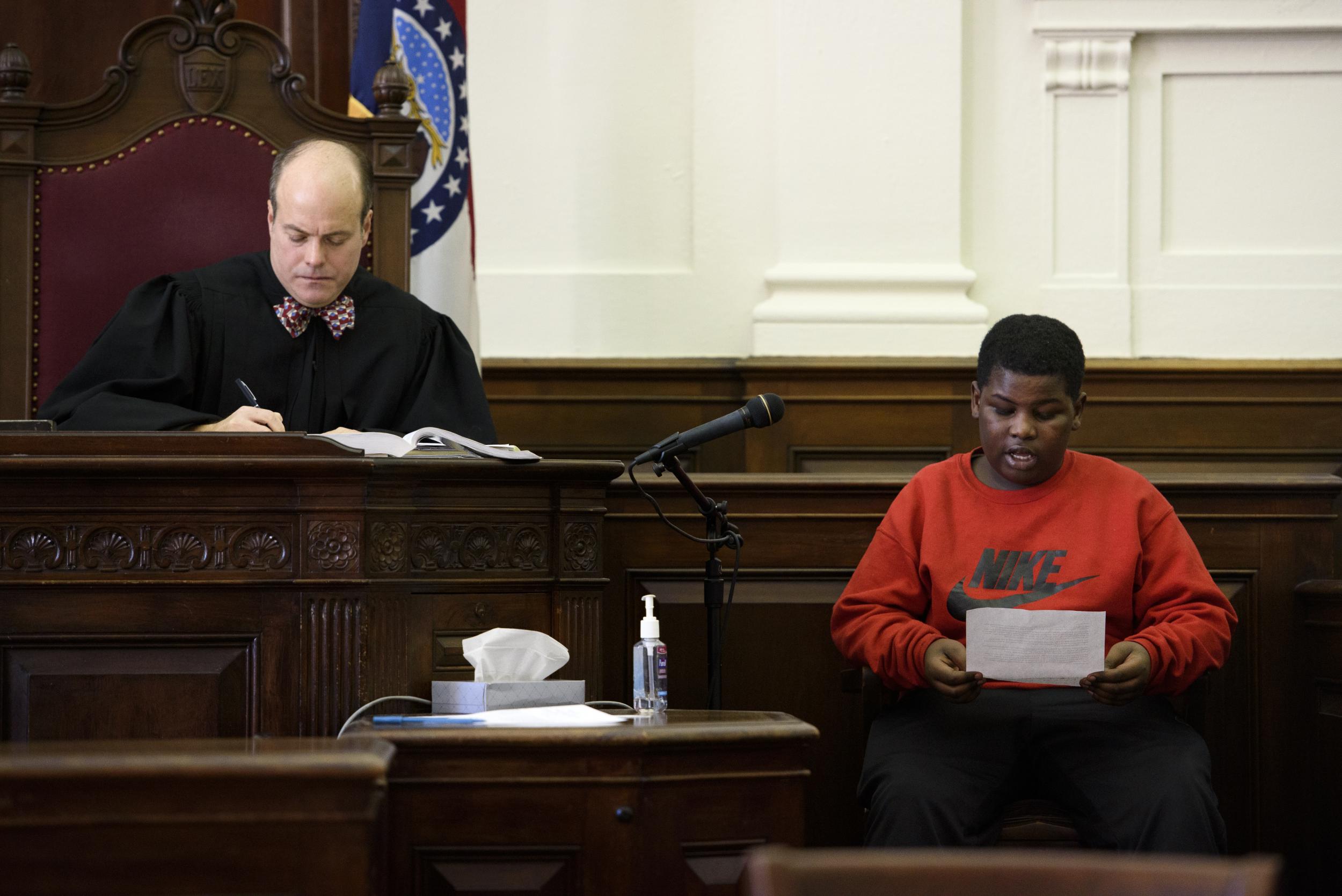

On a Friday morning in November, Whittier, in an orange jumpsuit, his hands and feet shackled, walked into the courtroom of circuit judge Thomas C Clark II for sentencing.

Reggie walked to the witness stand. The teenager opened a piece of paper, held it with both hands, took a deep breath and read aloud.

“You took a person who was like a mother to me, one of my biggest supporters,” Reggie said quickly, his face anguished. “If I could go back, I wish I could have stopped you.”

Zezima reported from St. Louis and San Diego. Paul reported from Fort Worth. Rich, Tate and Jenkins reported from Washington. The Washington Post’s Wesley Lowery, Kimbriell Kelly and Ted Mellnik in Washington contributed to this report.

© The Washington Post