Letting parents use new gene-editing technology to pick characteristics of their unborn child can be “morally acceptable” as long as it doesn’t increase social inequalities, an influential medical ethics group has said.

In a major report on the looming frontier of human gene-editing, the Nuffield Council on Bioethics (NCB) said it did not believe there was an ethical red line in tinkering with the genetic material that will be passed to future generations.

It also did not draw a distinction between using these techniques to tackle genetic diseases and for enhancing desirable physical or intellectual traits, so-called “designer babies”, so long as it meets strict ethical and regulatory tests.

The group, which appraises the ethical realities of new technology, called for the government to begin canvassing national opinion and said copies of the report would be sent to ministers and civil servants.

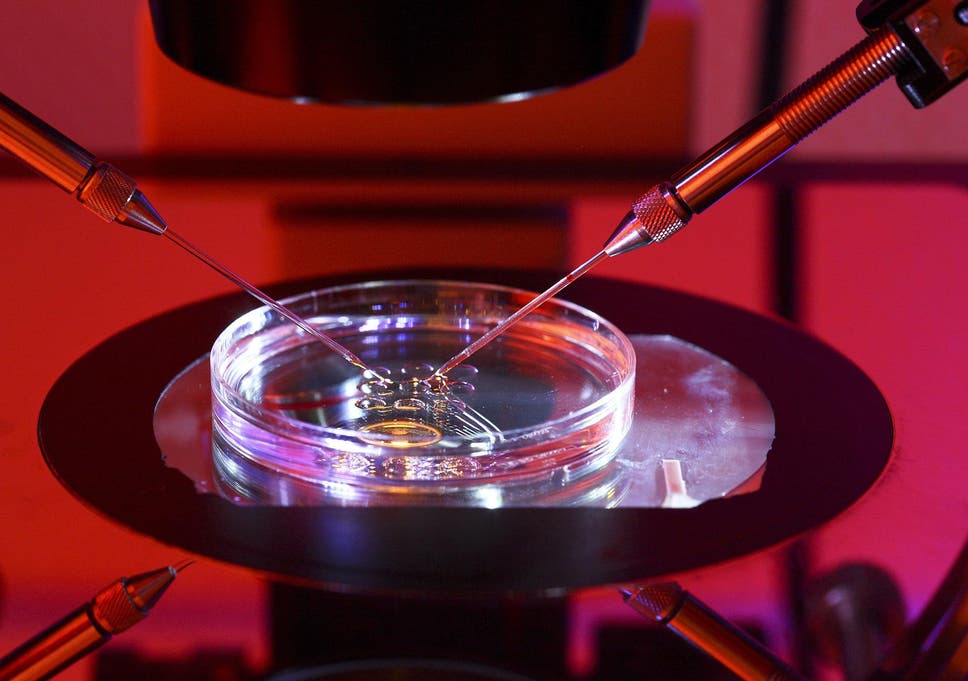

UK law does not currently permit any editing of heritable DNA – genetic information contained in an embryo, egg or sperm – though it is allowed for strictly controlled research purposes.

Even this, however, is hugely controversial and could have implications for people with diseases or less “desirable” traits if they become less common. Any change to the law would have to be subject to a national public debate and parliamentary legislation, as well as extensive testing for the safety of gene editing, the NCB said.

But a change is needed as we continue to expand our understanding of the human genome, and which gene instructions affect different diseases and traits. The arrival of precision genetic editing techniques like crispr has made correcting damaged or undesirable genes a real possibility.

Professor Karen Yeung, chair of the NCB report group, a law and ethics expert at the University of Birmingham, said these advances could have “profound consequences [which] affect the genetic make-up of society".

“There was an enormous range of views, including that we should not do this as to do this would be to take a step humanity should not take,” Prof Yeung said.

“We thought quite hard about this and came to the view that, in and of itself, intervening in the heritable genome would not be morally objectionable.”

This means “it should not be ruled out on principle” but for any gene-editing to be ethically acceptable two tests must be satisfied, the group said.

Firstly, changes must be made for the benefit of the health or welfare of the future person whose DNA is being edited.

This case can be clearly made for removing disease, but could equally be argued for enhancing socially advantageous traits like height or intelligence – though this is well beyond our current genetic knowledge.

The second test asks how these changes, which would be heritable by every one of that child’s descendants, would affect the make-up of our species. The NCB said that gene-editing “should not increase disadvantage, discrimination or division in society”.

This could rule out choices to enhance physically desirable traits, such as height or hair colour.

“It’s not often that you’re in a position where you can see a development like that coming towards you, and have enough time to think very carefully about how to go ahead with it – or not,” said Prof Leach Scully, one of the reports authors from the Policy Ethics and Life Sciences Research Centre at Newcastle University.

Any ethical debate will also naturally run against practicalities like funding. Many patients already report a postcode lottery in accessing IVF and fertility treatment based on their local NHS funding, and gene editing could initially be out of reach for all but the richest.

On this matter Professor Yeung said if funding inequalities “were to exacerbate social injustice, in our view that would not be an ethical approach”.

The report is published after a paper in the journal Nature Biotechnology raised concerns about the safety of using “molecular scissor” gene editing techniques like crispr.

It found that what were thought to be precise changes to single genes may actually affect other bits of the genetic code. This could raise the risk of cancers and other conditions – these safety risks have led international leaders to call for strict safety checks on gene-editing’s rollout.

Campaign group Don’t Screen Us Out was set up to warn about the “informal eugenics” of new screening technologies being implemented with little debate and oversight.

Routine pregnancy testing for Down’s syndrome has lead to 90 per cent of pregnancies diagnosed with the condition being terminated, the group said.

“Public health ethics are clearly not keeping pace with the development of new technologies, in fact, they haven’t even been at the races,” a spokesperson told The Independent.

“The consequences of antenatal screening on the Down’s syndrome community have been profound, enabling a kind of informal eugenics.”

It welcomed the call for a debate but said it must meaningfully involve groups affected by genetic diseases like Down’s.

Fiona Watt, executive chair of the UK Medical Research Council, said: “This is already a rigorously monitored area of research but it is vital that we continue to assess safety and feasibility before gene edits that can be passed across generations are permitted in people.”