Rainfall in Cape Town is a dramatic affair. In the winter wet season, ominous clouds and strong winds rumble in from the northwest, carrying with them the life-saving moisture of the Atlantic Ocean and dumping it in cold buckets on the city bowl. For days at a time, storms batter and flood the city and surrounding areas, so much so that the region’s first Portuguese moniker was Cabo das Tormentas: “the Cape of Storms.” But residents accept the thrashing. They embrace it, even, because the rainy season provides all the water there is.

During one of those winter storms, I huddled in a meeting room at the University of Cape Town, catching my breath after a wet sprint through the campus, which is built into the lower slopes of Devil’s Peak. I met with the hydrologist Piotr Wolski to discuss droughts. “I don’t know the workings of the city and the workings of the water supply systems—the pipes, and valves, and how it is managed—enough to be sure about this,” Wolski told me, “but I think that it is likely that Day Zero was never [going] to happen.”

The prediction had been that after years of an intense drought, Cape Town’s dams would be so depleted and local reservoirs so bone-dry that one day in the autumn of 2018—between March and May in the Southern Hemisphere—the city would cut off the water flowing to taps. That date, the “Day Zero” in question, captured the attention of Western press. Photographs of the brown, cracked mud flats where drinking water once flowed abounded. Papers wrote breathlessly about the doomsday scenario of mobilizing military assets to secure water distribution points, fearing the possibility of violent clashes over resources.

Day Zero didn’t happen—and as Wolski told me, it may have never been in the cards. But, over the course of a year, the idea really did deeply change the city all the same. Water scarcity, and the potential for a catastrophe, spurred upheaval and anxiety. During that time, a local government pushed a water-conservation agenda more ambitious than just about anything the world had seen. Cape Town faced political fallout and experienced widespread protests. Divisions between the haves and the have-nots in one of the most unequal cities on Earth became the center of discourse. The racial wounds of a post-apartheid country opened once more.

In its march to slash water consumption drastically, this metropolis of 4 million people also became a harbinger of how water will constrain global cities in the future, and how climate change will bring turmoil and a new slate of challenges to places where class and racial divides are deep. Day Zero is still hypothetical, but Cape Town’s reality will soon impact many global cities, where water will become a constant concern, and democracy will become contingent upon the taps.

Farther up the mountain, in a facility nestled between a memorial for the imperialist founding father Cecil Rhodes and a road named after Nelson Mandela, researchers at the university’s Future Water Institute consider how the water crisis has shaped the country and the city. “The way the city has managed it is by forcing middle-class South Africans—dominantly white, but not exclusively—to massively cut back on their water use,” says Neil Armitage, a civil engineer who is a lead researcher within the institute. “They struggled for a while until they came up with this Day Zero concept, which was really a warning that if we carried on behaving like we were, then the water was going to run out. That had the desired effect of making people a lot more serious about water, but it also had a horrible political backlash as well.”

The popular use of the phrase “Day Zero” likely began in early 2017, when it became clear that the worst drought in the region’s recorded history wasn’t going anywhere soon. In May, premier of the Western Cape and former Cape Town mayor Helen Zille declared the province, in which Cape Town is located, a disaster area, speeding up the implementation of the province’s “Avoiding Day Zero” plan. Local dam levels around that time dipped to one-fifth of their total capacity. Heading into summer, the situation became more dire and the political messaging grew more urgent. “If consumption is not reduced to the required levels of 500 million liters of collective use per day, we are looking at about March 2018 when supply of municipal water would not be available,” Cape Town Mayor Patricia de Lille told her constituents in October.

As the warnings escalated, so too did the restrictions. The Level 4 restrictions implemented in May 2017 imposed a recommended overall-consumption limit of 100 liters per person per day, prohibited irrigation with drinking water, and discouraged or banned other types of recreational water use. Level 4b restrictions, implemented in July last year, tightened that recommended limit to 87 liters per person per day, advising residents to take steps like limiting showers to two minutes, reusing shower water to flush toilets, and conducting “wipe downs” instead of showers.

The city announced Level 5 restrictions in September, and those rules hardened the 87-liter-per-day limit. Aggressive fines for households that consumed more than 20,000 liters in a month were imposed, along with “water-management devices” to cap their usage. As they stand now, the Level 6B restrictions created by the city of Cape Town in January 2018 are supposed to limit residents to 50 liters per day, slash agricultural use by 60 percent below last year’s usage, aggressively push water-management devices and fines, and encourage the use of new fittings and other devices to minimize water waste.

But those increasingly strict measures were only part of the Capetonian defensive against Day Zero. In addition to the official measures, political leaders in Cape Town and the Western Cape launched a social campaign, designed not only to promote water thriftiness, but to shame big users. Stickers and flyers urging conservation practices saturate Cape Town and its bathrooms, even welcoming international guests at the airport. During the height of the summer dry season, de Lille personally visited some of the homes that used the most water. In January of this year, according to South African news outlet eNCA, Zille encouraged residents to inform on water-hogging neighbors and become “water impimpis”—a callback to an apartheid-era term for black South Africans who spied for the white-dominated government.

as Armitage told me, the water-saving strategies and social-engineering plans embraced by local politicians didn’t make many friends on the ground in the city. Almost immediately after city leaders announced the first Day Zero predictions, they came under heavy scrutiny from citizens and activists, especially among Cape Town’s communities of color. Many in labor, socialist, and leftist organizations in the region didn’t believe Day Zero was even a thing. Elements from those organizations created the Cape Town Water Crisis Coalition, which protested Day Zero as propaganda designed both to cover up faulty city water management and to deny expanded access to low-income communities.

“The purpose of all this (mis)information is clear: shifting blame from government,” reads an op-ed posted to the Water Crisis Coalition website shortly after the 50-liter household limit was passed by the local government. The Coalition asserted that “in fact, all tiers of Government is complicit through lack of foresight and mismanagement of our water resources.” Through a series of intense protests and heated confrontations with officials in the summer, members of the group stressed that a mobilization of citizens on the order of the old anti-apartheid movement would be required to create the political change necessary to secure the water future of the Western Cape and South Africa. A common refrain in their rallies, marches, and street arguments with Democratic Alliance politicians, the Coalition’s slogan is “water for all or the city must fall.”

Throughout the Day Zero crisis, that slogan proved to be a significant threat for the Democratic Alliance, or the DA, Zille and de Lille’s party that runs the Western Cape and Cape Town. The DA’s party boss, Mmusi Maimane, has pushed back against those criticisms, and defended his party’s governance. “Day Zero is still a very real possibility during the 2019 summer months if we do not have significant rainfall this winter,” he said earlier in March. “I want to reiterate, and cannot stress enough, that we need to keep at current consumption levels until at least after the winter rainfall.”

Still, the management of the crisis has also sparked criticism from the African National Congress, or the ANC, the dominant party in the country. As the only opposition party to control a province, the DA is certainly used to strife with the ANC, but now old struggles over resources have brought that tension to a breaking point.

The ANC is the party of the Mandelas, a national emblem of black independence and sovereignty rooted in a mix of socialist, social-democratic, and black-nationalist ideals. The DA, however, embraces a more American-style market-oriented centrist liberalism. Deeply complicating the dynamic between the two parties is that the Western Cape is the major center of white demographic strength and political clout in the country, and that the DA—while embracing a membership of blacks, “coloured” multiracial descendants of indigenous peoples and Asian immigrants, and whites—often finds white leaders near or at the top.

From the moment Day Zero became a political problem, it deepened the rifts between the parties. Under South Africa’s Constitution, the ANC is responsible for providing water to all citizens, but the actual infrastructure and services in the Western Cape falls upon the DA to manage. This arrangement would seem to necessitate cooperation, but in reality that hasn’t been the case. The two sides have bitterly smeared one another, blaming the collapse of a number of schemes to boost water supply on the intransigence or ineptitude of opponents. In one case, DA leaders criticized the ANC-led national government for reportedly rejecting assistance from Israel, which employs advanced conservation techniques in its water infrastructure. The South African government is officially aligned in support of Palestine, and has now engaged in a boycott of Israel for decades.

The bigger disruptions for the DA came from local backlash. Last July, when confronted on Twitter by a black user who said that black residents in areas without running home water had experienced Day Zero from birth, Zille, who is white, responded with: “It must be a relief that you weren’t burdened by the legacy of a colonial water-piping system.” Zille, who’s faced harsh internal and external criticism for previous statements in defense of colonialism, this time suffered a rebuke from party boss Mmusi Maimane, and has since been officially suspended from party activities.

Things haven’t gone much better for de Lille, who has faced numerous allegations of mismanagement since the beginning of the water crisis. While management of Day Zero itself hasn’t often been recounted among the official reasons party insiders in the city have tried to oust de Lille from the mayor’s office, the crisis was nonetheless a backdrop to a concerted effort by DA insiders to do so. De Lille faced multiple proposed votes of no-confidence and an ongoing legal struggle, but neither of those efforts has come to completion. Still, de Lille is largely a contentious figurehead now, after she was stripped of her authority over the water crisis last year and removed of all her executive power.

That rhetoric reached fever pitch in May 2018, as the city proposed massive new water tariffs for households, with the highest proposed hikes coming for uses under 6,000 liters per month. For opponents, that proposal epitomized the policy and communication problem that’s plagued the DA. It would certainly raise revenues for water sourcing and cut water use—but only by placing the biggest burden on households in the lower half of the income distribution.

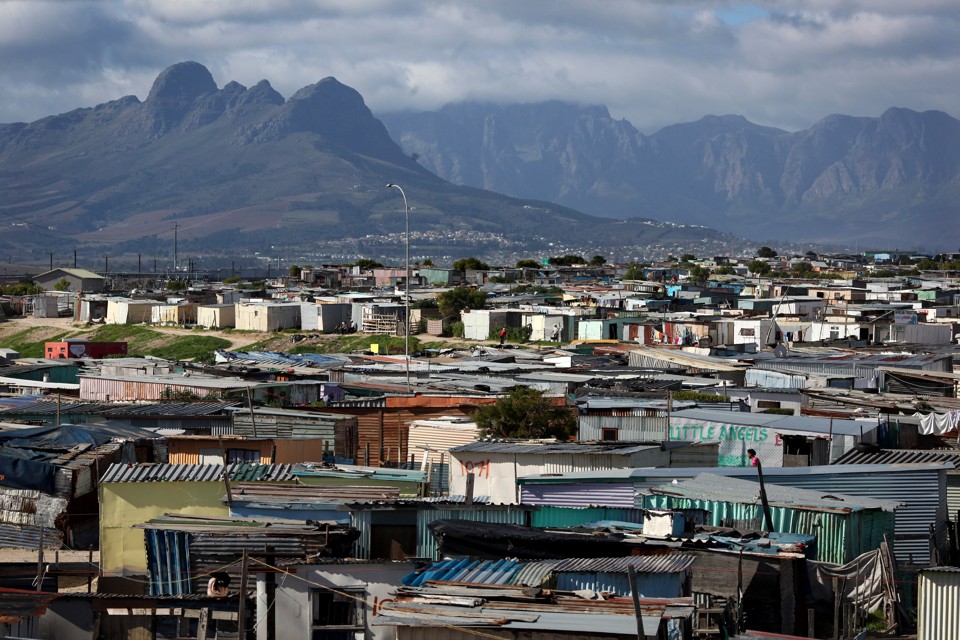

Residents in well-apportioned suburbs pointed fingers at the mostly-black and poor residents of the so-called “informal settlements”—the tin-roofed, sprawling shanties that ring the outskirts of the city—despite the fact that these settlements use the least water per capita of any place in the province. And lacking internal plumbing and sewage, residents in the informal settlements often see in the city’s elites and governing class a neo-colonialist force, doling out resources at whim and mismanaging the commons.

For a cosmopolitan travel hub that has built a reputation as a true social and ethnic international melting pot, Cape Town’s social and political problems during its water crisis boiled down to the same fundamental issues that underpin its past as an icon of apartheid: white versus black, and poor versus rich. During a 2014 investigation into water access, the South African Human Rights Commission outlined the problem in Cape Town. “Those areas which lack water and sanitation mirror apartheid spatial geography,” the commission’s findings read. That is to say that even the built water infrastructure is based on exclusion.

Day Zero uncovered that deeper nature, and punctured the myths of harmony that have sustained Capetonian culture for more than 20 years. But, paradoxically, these re-opened rifts mobilized citizens, and did seem to avert the Day Zero scenario. Was it worth it?

Fill up an empty two-liter soda bottle with water. Now fill up another. Fill up another and another and another. Top up 170 bottles, running an average kitchen faucet for 40 minutes, and you’ll come close to estimating just how much water the average American consumes every day. Between things like drinking, tooth brushing, showers, toilet-flushing, doing the laundry, and hitting your work outfit with a little steam, Americans use somewhere around 90 gallons, or 340 liters, of water every 24 hours. That’s more than 700 pounds of water per day, and that’s not even counting what goes into the food you eat or the thirsty maws of the industries and services that sustain you.

Luckily, there’s quite a bit of water on Earth. It covers 70 percent of the surface of this great blue ball. It’s in the puffy clouds in the sky and gurgling through chthonic rivers hundreds of feet below us. And although the freshwater humans can drink is much more limited, it’s still incredibly vast. Human ingenuity has tapped that vastness. In a way, cities are just sophisticated delivery systems for water, using millions of miles of pipe across the globe to move that precious liquid from source to faucet, managing both supply and demand in order to keep the flow going.

It continued to rain as I sat in the current nerve center of Cape Town’s vast water-moving system. The computer screen in Deputy Mayor Ian Neilson’s office within the municipal building in Cape Town is jammed with windows full of water-status dashboards, presentations on Day Zero, and projections of dam levels. Having wrested most of the official powers of the executive office from de Lille, Neilson is the chief administrator of the city and one of the opposition party’s most powerful leaders. But here in his office, he played the role he’s been most familiar with over the past few years in the city government: a bureaucrat whose job is consumed by the minutiae of water.

Neilson and I discussed all the ways that the city had managed its delivery system during its most troubled year. “I think our situation’s stabilized,” Neilson told me. “It’s very clear we’ve avoided the worst, absolutely, this year. We are now into the rainfall season without having run out of water.” As the rest of the rainy season plays out, Neilson says that the game of the city government is monitoring the situation, persisting with tight restrictions, and continuing to urge intense water-conservation practices until it’s clear the reservoirs can again support regular water usage. Right now, the water usage of the average Capetonian sits at about 125 liters per day, a dramatic decrease from the 200 daily liters of last year. Both of those levels sit below the average of developed cities worldwide, and well below the standard American usage of 340 liters.

“Cape Town is an example of what is achievable under these conditions of stress,” Neilson continued. “People’s relationship to water changed. You saw how we got the consumption down dramatically. It’s only possible because millions of people have proactively gone out and worked very hard to get their consumption down and changed their habits dramatically.”

But, as even Neilson acknowledges, the extreme social engineering brought about by the Day Zero campaign is unlikely to be a long-term solution to future water problems in Cape Town. Nor will it necessarily prove to be a sustainable model for other cities facing water shortages.

For one, the ongoing drought in the Western Cape, although it seems to have been alleviated somewhat with heavy rains this winter, might only be the harbinger of worse weather patterns to come. Almost all of the vital rainfall in Cape Town is governed by a specific dynamic of weather systems off the southwestern coast of Africa, and each of these is in turn mediated heavily by the temperature of the ocean, which is now rising thanks to climate change.

“The climate projections for Cape Town indicate essentially a relatively consistent reduction in the amount of rainfall in Cape Town,” Wolski told me. “In the best case, it would be rainfall that is similar to what we have. But most of the projections indicate reduction.” It’s exceedingly difficult for climate scientists like Wolski to accurately model the actual future conditions of such an intricate and delicate specific climate system like that of Cape Town—indeed, there are signs that this drought may be part of a long-term trend of increasing rainfall—but Wolski says that eventually warming will win out. And even if future rainfall patterns do manage by some unknown dynamic to stay similar to current levels, increased temperatures driven by anthropogenic climate change mean increased evaporation and baseline-higher water requirements for people, industry, and agriculture.

As a result, Cape Town is already facing the kinds of resource crunches that will define a hotter Earth. It joins other metropolises of South and East facing similar fates. Environmental think tanks and journalistic outlets have published lists of cities that look likely to run out of water in the near future: São Paulo, Brazil, which faced its own Day Zero situation just a few years ago; Bangalore, India; Beijing, China; Cairo, Egypt; Mexico City; and—surprisingly, given its climate—Moscow, Russia. While each city has a very different set of reasons for its water woes, ranging from pollution to poor infrastructure to poor planning to desertification and drought, they all share a common challenge: Climate change will likely make the task of providing water harder, the populations thirstier, and the people angrier, even as many of the cities grow.

These pressures do not portend well for the developing world’s cities, which face a paradox in a time of tightening global resources: Municipalities are often giant businesses that provide a set of limited resources, and that also moonlight as the lowest levels of government. Resource shortages are thus politically and socially destabilizing in cities. The axes of power and partisanship within them can shift quickly when the faucets run dry.

Take, for instance, São Paulo, where deforestation and pollution of local water sources brought the city and peripheral municipalities to the brink of disaster in 2014 and 2015. The exact factors that stripped the city of fresh water were certainly different from those in Cape Town, but the topography of conflict in both areas is similar. The shortages in São Paulo sparked street fights, citizen mobilization, and major political dissent in the city.

In a thesis on the dynamics of politics and political mobilization during São Paulo’s water crisis, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology researcher Isadora Araujo Cruxên found that water-supply management was “a deeply political issue.” Just as the Coalition arose in Cape Town, the Alliance for Water (Aliança pela Água) and the Collective for Water Struggle (Coletivo de Luta pela Água) emerged in São Paulo and its surrounding areas. For these groups, the prospect of water shortages, along with an oppositional politics demanding water as a human right, proved to be the catalysts for coalition building—and a potentially dangerous platform for political movements in the future.

“The water-supply crisis has served to awaken dormant civil society forces that had been relatively removed from water decision-making in the state,” Cruxên writes. “The efforts of the Alliance and the Collective contributed to deepening democratic participation in water-related processes during the supply crisis.”

While she did not find that the Alliance and Collective necessarily made major electoral waves or dents in the national consciousness, Cruxên did find that water shortages proved to be instant bridge-builders for disparate social and political groups. “The message is that these political-organization projects can coexist and there are opportunities for these movements to collaborate strategically,” Cruxên told me by phone, “and to provide counter-narratives to some of the dominant narratives in the water and sanitation sectors that have been in terms of international governance dominated by technical experts and by business experts.”

The evidence from Cape Town squares with Cruxên’s hypothesis. Even with differences between the two cities—São Paulo is truly a global megalopolis with more than 20 million inhabitants in its metro area, and its hydrology is obviously much more expansive, complex, and affected by pollution—there are similarities that illustrate how global, water-based political conflicts might arise. Both are staggeringly unequal cities in countries where inequality is rampant. That inequality manifests both in social stratification and in the development of water-delivery systems to those different strata. In Cape Town, as in São Paulo, access to clean water is a problem that can rise from an inequity to a humanitarian crisis in no time at all. And, in both cities, that possibility is already mobilizing marginalized communities and becoming a driver for change.

A 2015 study from the South African Water Research Commission finds that even before the Day Zero crisis, water already might have been the most important mobilizing force in the country. “In 2012 the frequency, geographical spread and violence of service delivery-related social protests in post-apartheid South Africa reached unprecedented levels,” the authors write. They find that four factors presage water protests: economic disparities and marginalization, water-delivery problems, communication breakdowns between authorities and the people, and the presence of active and latent organizing efforts and structures. An additional study by the University of the Western Cape researcher Ndodana Nleya finds that service-delivery issues related to water are the main catalysts increasing the likelihood of protests in Khayelitsha, an informal settlement in southeast Cape Town. These issues are perhaps only partially affected by the Day Zero crisis, but they sow unrest in an area where water will be a political force for the foreseeable future.

Essentially, what the literature tells us is that the very structure of Capetonian life creates conditions for upheaval in the event of a water crisis. Mirroring class conflicts in the 20th century, the idea that access to water is a human right has become a driver of solidarity, hardening ad-hoc activist groups into major political movements. Extrapolating to the rest of a warming world, where racial and class barriers have been built into zoning and infrastructure, the uneasy detentes of segregated spaces and places could become new zones of conflict. All you have to do is remove water.

Neilson didn’t respond immediately when I asked him if Day Zero was ever really going to arrive. He turned his widget-crowded screen to me and showed me a graph of the dam levels in the city. A line on the graph indicated the city’s projected water levels absent additional rainfall. Another line showed the projected use of water by Cape Town citizens. When it bisected the dam levels, sometime in what would be the middle of spring in the Northern Hemisphere, the line turned red. That was Day Zero. But another line on the graph indicating the actual water usage of the city over the previous eight months curved gently, and then ever more sharply away from the trend line. It leveled off well above the dam levels. Neilson had given me his answer.

I tried another tack. How would he respond to charges from activists in the city that tariffs and the increasingly restrictive water regulations in Cape Town had effectively abandoned the constitutional promise of access to water? He took a breath, and spoke. “We accept, even given all of that, that people have a right of access to water, and there are minimum amounts of water that you need to survive,” he said. “So we provide free water to poor households. 10.5 kiloliters a month they get free.”

“Although the rainfall may be free,” he continued, “there are costs involved in terms of storing that water, treating it, and distributing it. To get to understand that, that just because you can open a tap—a whole lot of stuff had to happen before you get there. You don’t see that there’s all of this stuff behind this to bring that to be there. There’s a whole massive system and that’s where all the costs are. That’s the most simple explanation I can give.”

The rain continued for days. In fact, so far this winter the rainfall has helped raise the dam levels to just below 60 percent of capacity, which should put off the next crisis point for some time. Cab drivers, students, waiters, and tour guides spoke incessantly of the Day Zero crisis—and with plenty of real venom—but they mostly spoke of it as a thing that had happened, an event that was now being relegated to the past. One of the last bellhops that I spoke to about it sucked his teeth as he jogged off. Didn’t matter to him, he told me, because he had to make the bus home to Khayelitsha.