SINCE THE financial crisis a decade ago, the annual task of presenting Britain’s budget to the House of Commons has been an especially daunting one. Chancellors of the exchequer have had little to report but bad news, usually requiring them to impose spending cuts, tax rises or both. Yet on October 29th Philip Hammond came to Parliament with a cheerier set of announcements (see article). His hour-long speech was littered not just with giveaways but also with tax cuts, adding up to the least frugal budget since at least 2010. “The era of austerity”, he announced, “is finally coming to an end.”

It was a crowd-pleasing package at a crucial time. In the next few months Parliament will vote on whether to approve whatever exit deal, if any, the Conservative government strikes with the European Union. Losing that vote would mean a political crisis, and possibly a general election. Mr Hammond’s budget therefore needed to give Tory MPs an incentive to back the government in Parliament, and voters a reason to side with the Tories in an election, should it come to that. With his generous scattering of handouts and hints of more to come, he just about pulled it off. But a budget that got the government out of a tight spot this week also sowed problems for the future.

Mr Hammond’s generosity was not the result of a sudden big improvement in Britain’s economic fortunes. On the contrary, the economy is forecast to grow by a dismal 1.3-1.6% a year for the next five years, slower than most advanced countries—and that is assuming an orderly exit from the EU, which is far from certain. Instead, the chancellor’s splurge was made possible only by the fact that the Office for Budget Responsibility, which produces the forecasts he uses as the basis for his calculations, found a treasure trove of loose change down the back of the national sofa. It revised up its estimates of tax revenues, possibly because the economy is bigger than it was expecting, giving Mr Hammond up to an extra £20bn ($26bn) a year to play with.

He gratefully spent the lot, and for the most part did so wisely. The National Health Service, straining under the burden of an ageing population, got almost all of it. Universal credit, the well-designed but underfunded plan to simplify welfare payments, got a small boost in order to ease the worst of its problems. Little grants were made to spruce up classrooms, fill in pot holes and so on, while targeted bungs were directed towards Northern Ireland, ten of whose MPs prop up the government.

These giveaways were accompanied by tax cuts of varying merit. Small companies will get help with paying their business rates, in an attempt to spruce up Britain’s high streets. Bigger firms will benefit from the bringing forward of a tax break on investment. Income-tax thresholds will be raised earlier, mainly helping the well-off, and fuel duty was frozen for the ninth year running (odd from a government that wants to limit climate change). A new levy on big tech firms, which pay almost no tax in Britain, was one of few tax-raising measures.

This budget had two big political messages—all the more effective in coming from a not very political chancellor. The first was aimed at voters. After almost a decade of austerity, the public are so sick of cuts that a growing number are flirting with Labour, which promises to bring an end to the squeeze. Mr Hammond’s new pitch is that the Tories are also ready to end austerity—and that unlike Labour, they would do so without raising taxes or turning the economy upside down. His announcement of the abolition of the private-finance initiative (PFI), under which firms build and run public projects, sometimes at eye-watering cost to the taxpayer, was another move onto opposition turf. A sign of the budget’s political success was that Labour found little in it that it could oppose. This was a budget designed with the possibility of an election in mind.

The second message was aimed at Conservative MPs. Those who dislike the compromises that the government is being forced to make in Brussels—from ultra-Brexiteers, who fear a sell-out, to diehard Remainers, who hope for a second referendum—are threatening to vote against any deal that the government brings back. Mr Hammond made clear that this week’s giveaways were predicated on a deal and that, if no deal were to happen, all this would be at risk. The glimpse of sunlit uplands is intended to remind MPs what is at stake if they decide to roll the dice and vote down the Brexit deal.

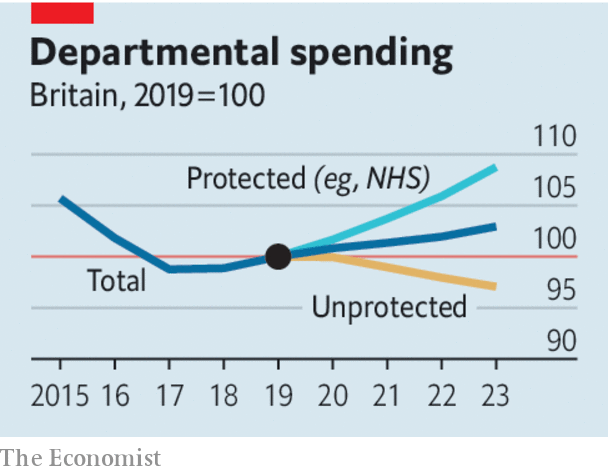

Hence, this was a riskier budget than it may have looked. Declaring the end of austerity won approving headlines the next day, but it is really only half true. Because of health, overall spending is set to rise again, yet almost all other departments will continue to endure flat or falling budgets. In other words, in most parts of government austerity will continue. After this week, every spending cut will not be seen as a regrettable necessity but as a broken promise. The pressure to loosen the purse-strings will grow—especially after March 29th, when people will expect to see the Brexit “deal dividend” that Mr Hammond promises when Britain leaves the EU.

In truth, the scope for increasing spending is very limited. There is no reason to think that the revised forecast that was the basis for this week’s splurge will be repeated—indeed, the next time the estimates are revised it could even be reversed. The economy itself shows little sign of rapid improvement. Though employment is high, productivity growth remains weak. Brexit, just five months away, will create at best a slow puncture and at worst, if no deal is reached, a dramatic bang.

Posterity before austerity

Even without Brexit, Britain’s long-term fiscal position is unsustainable. Within two decades the country will have 50% more over-65s than today, even as the scope and cost of their medical treatment is growing. Either taxes will have to go up, or spending will need to be spread so thinly that recent austerity will look like a picnic. This was never going to be the week that the government came up with radical answers to this conundrum. But by telling voters that good times are just around the corner, it has left them unprepared for the hard choices that, sooner or later, Britain will have to confront.