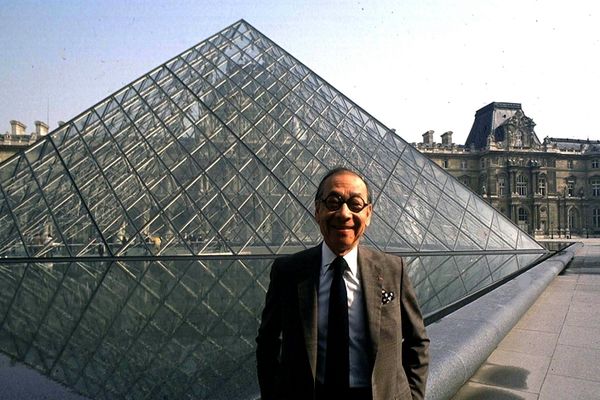

I.M. Pei, an American modernist architect regarded as one of the world’s leading designers of civic centers and cultural institutions, including the National Gallery of Art’s East Building, the glass pyramid at the entrance to the Louvre in Paris and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland, died May 16 at a hospital in Manhattan. He was 102.

His son Li Chung “Sandi” Pei confirmed the death but did not provide a specific cause.

Considered one of the most significant and prolific architects of the 20th century, the New York-based designer left a legacy of notable buildings that span the globe. His significant works include the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in Manhattan (1979 to 1986); the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas (1982 to 1989); the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong (1982 to 1989); and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar (2003 to 2008).

“You cannot talk about architecture in the last 60 years without talking seriously about I.M. Pei,” said Robert A.M. Stern, a former dean of the Yale University School of Architecture. He referred to Mr. Pei as perhaps the greatest modern maker of monuments, and said of Mr. Pei’s legacy: “It’s not a single building. It’s his work over a generation of time and his logical and relentless pursuit of the highest degree of excellence.”

Mr. Pei has been credited with rescuing modernist architecture, typically stark buildings with little or no ornamentation, from its reputation as a cold and forbidding art form. He did so by creating open public spaces that made people feel welcome and by designing museums that were bright and inviting, rather than a collection of small, dark rooms.

Throughout his career, Mr. Pei favored simple materials and simple shapes for the basis of his elegant designs. “The simpler the solution, the more powerful it is,” he once said. He started with uncomplicated geometric forms, using stone, concrete, glass and steel to transform them into dramatic and sculptural light-filled spaces.

“More so than any other modern architect of his generation, he was able to make modern architecture friendly and approachable to a wide audience,” said Pei biographer Michael Cannell. “He went a long way toward translating modern architecture on behalf of a public that may not otherwise have been disposed to appreciate it.”

Mr. Pei was born in China and earned degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard’s design school, and spent his early career designing low-income housing for a real estate developer in New York.

He went into business for himself in 1955, but his breakthrough came nine years later when he was the surprise victor in a contest to build a library to honor John F. Kennedy. It was one of the most coveted architectural commissions in the world, and Mr. Pei, a relative unknown, defeated the biggest names in architecture, including Philip Johnson, Mies van der Rohe and Louis Kahn.

When it came to securing his commissions, Mr. Pei’s personal skills were just as important as his architectural abilities. During discussions about the library, he insisted to Jacqueline Kennedy that he was “totally unqualified” for the project. Yet with the taste of his potential client, the former first lady, in mind, he had his entire office repainted white and placed a single vase of fresh flowers in the reception area.

When she noticed flowers, she said, “My, that’s a beautiful bouquet. Do you always have those?” Mr. Pei responded, “Oh no, we only got those for you.”

“He knew how to use his innate charm to his best advantage,” Cannell said. “You can imagine for Jackie Kennedy, surrounded all her life by overbearing men, how charmed she could be talking to a man like Pei.”

Kennedy said one of the determining factors in choosing Mr. Pei was that she saw him as an underdog, as her husband had once been viewed in politics. Johnson once said of Mr. Pei, “All his jobs were feats in diplomacy. He performs incredible political footwork that none of the rest of us have any idea about.”

Although the Kennedy library commission catapulted Mr. Pei into the national spotlight, it was one of his biggest disappointments. Controversy over the design and the site dragged on for years, and Mr. Pei lost all passion for the building. Although his firm saw the project through to the end, Mr. Pei became despondent and moved on to other commissions.

When the library finally opened in 1979, 15 years after its commission, it wasn’t to the level of the original design and turned out to be one of Mr. Pei’s least-distinguished works. “It should have been my best and most important project, but it was not,” he once said. “It’s a sad story, and one of the few projects that have failed in my opinion. I lost the client.”

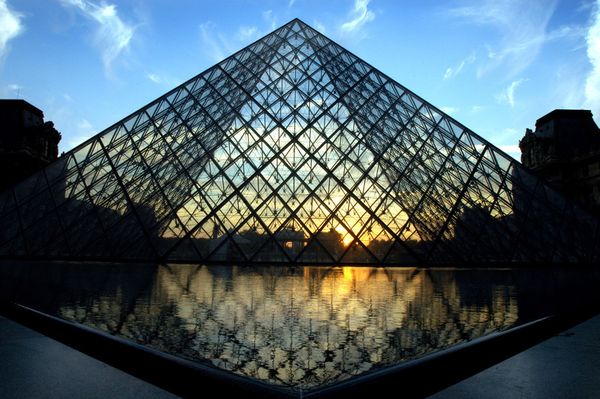

Mr. Pei’s original design for the library included a glass pyramid, a design element that would reappear years later at the Louvre in Paris and become a signature form.

Despite the unfulfilled promise of the Kennedy library, Mr. Pei’s selection as its designer and the many commissions that followed brought him an extraordinary public profile and celebrity. One of the most important was the addition to the National Gallery of Art (1968 to 1978).

Mr. Pei was hired by National Gallery benefactor Paul Mellon to design the East Building. The project was regarded as difficult because it needed to fill many sensitive requirements. It needed to complement — not upstage — the classical structures of the adjacent West building and the nearby Capitol, and it had to be designed to sit on an awkward, trapezoidal plot of land.

Mr. Pei solved the complex problem with a simple solution. “I sketched a diagonal line across the trapezoid and produced two triangles. That was the beginning,” he said in a 1999 interview with the publication School Arts.

The finished product, a building made of steel, glass and marble with an H-shaped facade and a knife-edge corners, introduced modernism to the Mall while blending seamlessly with its neoclassical neighbors. Opened in 1978, it was named one of the 10 best buildings in America by the American Institute of Architects.

French President François Mitterand was so taken by Mr. Pei’s work at the National Gallery that he handpicked the architect to renovate and reinvigorate the Louvre in 1983.

The project, which Mr. Pei referred to as “the greatest challenge and the greatest accomplishment” of his career, tested nearly every political instinct of the soft-spoken architect, who was seen as an American interloper at a cultural landmark that housed the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo.

When Mr. Pei revealed his design for the addition to the centuries-old palace, which included a 70-foot glass pyramid to serve as the museum’s main entrance, French politicians, historians and citizens were outraged. Newspaper editorials compared the design to “an airport or drugstore” and said the pyramid would “reflect the colors of the sky, like the Ewing building in ‘Dallas.’ ”

The French newspaper Le Monde referred to it as “an annex to Disneyland.” The museum director resigned in protest.

It was ultimately Mr. Pei’s understanding of the volatile political environment in France that saved the Louvre project. His key insight was to provide progress reports both to Mitterand, a socialist, and to his conservative rival, then-Paris Mayor Jacques Chirac. Indeed, when Mitterand was forced to share power with Chirac, who was elected prime minister as part of a transition government, Mr. Pei’s investment paid off as he had gained the support of both political sides as well as the museum’s curators.

Even French movie star Catherine Deneuve visited his design studio to lend her support. Later, Mr. Pei recalled, “All you need is the support of a dozen people like that.”

Ieoh Ming (“to inscribe brightly”) Pei was born in Canton, China, on April 26, 1917. His father was a prominent banker; his mother, who died when Mr. Pei was 13, was a flutist. He was the eldest of four children.

After the death of his mother, Mr. Pei moved with his family to Shanghai, where his interest in architecture began with a fascination with the growing cityscape. Once, while walking with an uncle past a new hotel, the younger Pei became so inspired by the building that he stopped walking, sat down and started sketching.

As a boy, he attended the prestigious St. John’s Middle School and spent several summers at his family’s private residence and garden in Suzhou, a Chinese town often referred to as the “Venice of the Orient.”

Despite his father’s wish that he become a doctor, Mr. Pei left for the United States in 1935 to study architecture. He earned a bachelor’s degree in architecture from MIT and a master’s degree in architecture from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus school of design, a movement that advocated architecture without ornamentation and function over form, ran Harvard’s design school.

Mr. Pei’s Harvard classmates included some of the most distinguished architects of his generation: Edward Larrabee Barnes, John Johansen, Philip Johnson and Paul Rudolph.

The outbreak of World War II and the communist takeover in China prevented Mr. Pei from returning to his homeland. He became an American citizen in 1954.

In 1942, he married Eileen Loo, a Chinese American from Boston who was a landscape architecture student at Harvard. She died in 2014. In addition to his son Sandi, survivors include two other children, Chien Chung “Didi” Pei and Liane Pei, all of Manhattan. Mr. Pei’s eldest son, T’ing Chung, died in 2003.

Mr. Pei began his career in New York, in the field of commercial development, working as an in-house architect for William Zeckendorf, one of the largest real estate developers in the United States.

In this position, Mr. Pei gained the practical experience of working with large-scale urban renewal and low-income housing projects all over the country.

When Zeckendorf got into financial trouble, Mr. Pei took the opportunity to go out on his own. In 1955, he established his own firm, I.M. Pei & Associates, which later became I.M. Pei & Partners, then finally, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners.

The firm’s first important project was the National Center for Atmospheric Research, at the base of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. Inspired by American Indian cliff dwellings, Mr. Pei designed a number of poured-concrete towers, tinted with red sandstone to help them blend into the mountainside rather than distract from it. It was the first time the young architect was able to look at architecture as an art form.

Years later, he would refer to the project as the beginning of his professional life, describing it as “very, very amateurish on my part, but very important.” The building impressed the philanthropist Paul Mellon enough for him to pick Mr. Pei to design the East Building.

Despite ensuing successes, setbacks on the John Hancock Tower commission in Boston (1967 to 1976) almost sank Mr. Pei’s firm.

The 60-story glass skyscraper was designed by Mr. Pei’s partner, Henry Cobb. Before the building was completed, windows began popping out and falling to the sidewalks below.

With black-painted plywood panels replacing the windows during repairs, the building earned many nicknames, including “Plywood Palace.” Although the firm was eventually cleared of any fault, the damage had been done. Mr. Pei later said of the incident: “It was a disaster. After John Hancock I had to go abroad to find work. No one would talk to me.”

Forty years after leaving China, Mr. Pei returned to his native land to work. The Fragrant Hill Hotel (1979-1982), is a modest, low-rise building northwest of Beijing that Mr. Pei undertook in hopes of creating a benchmark design for future Chinese architecture. But dealing with the Chinese government and bureaucracies presented many obstacles, and the building ultimately wasn’t executed in the way Mr. Pei intended. When the project was completed, the architect walked away disappointed.

The Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, a soaring, 70-story steel and glass skyscraper, had special significance for Mr. Pei; he took on the project to honor his father, who served as a manager for the bank. However, the elder Pei died a few years after the commission and never saw the final project.

Mr. Pei retired from his firm in 1990 to become a sole practitioner. He spent his semiretirement working as a consultant for his company, assisting at his sons’ New York-based architectural firm and taking on projects that brought him personal pleasure.

Mr. Pei was an unlikely choice to design the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but the founders of the museum believed he would add credibility to the project.

At the time of the commission, Mr. Pei confessed to preferring Beethoven and that he had little experience with rock-and-roll other than asking his children to turn down the volume. (In one interview, he referred to John Lennon as “Jack.”)

To familiarize himself with the genre, Mr. Pei attended rock concerts and visited Elvis Presley’s Graceland, which he deemed “a horrible place” but said “it did not dim my interest in rock-and-roll.”

Perhaps the finest example of Mr. Pei’s artistry came late in the designer’s life. The Miho Museum near Kyoto, Japan (1996), sits on a remote mountain in the middle of a nature preserve. Inspired by a 4th-century Chinese poem, the architect designed a 150,000-square-foot limestone, glass and steel structure, of which only a portion can be seen peeking through the hilltops; 95 percent of the building is buried.

To echo the paths of Japanese gardens and temples, Mr. Pei designed a tunnel carved though the mountain, leading to a bridge, which leads to the museum.

But it was the new wing of the Suzhou Museum in China (2006) that was of personal significance to the architect. Not only did the location take him back to the ancestral gardens of his youth, but this time he also was able to share it with his children; two of his sons worked with him on the project.

Mr. Pei’s final masterpiece was the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha. Opened in 2008, when Mr. Pei was 91, the 115,000-square-foot building, constructed on a man-made island just off the waterfront, blends modernism with ancient Islamic architecture.

Mr. Pei was awarded the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal in 1979, and the Pritzker Award for architectural excellence in 1983. He used the $100,000 Pritzker prize money to establish a scholarship fund for Chinese men and women to study architecture in the United States, with the condition that they return to China to practice. He was also the recipient in 1993 of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award.

More than 40 years after the East Building opened, Mr. Pei’s famous knife-edge and the carving of his name on a marble wall remain the two most admired surfaces in the museum, both with perpetual smudges from handprints.

But back in 2003, when Mr. Pei was in Washington to celebrate the building’s 25th anniversary, he felt, even then, that high praise of the building was premature.

“Architecture is stones and brick, concrete and steel,” he told The Washington Post. “Architecture has to endure.”

Read more Washington Post obituaries