On Monday, Apple, Facebook, YouTube, and Spotify “banned” the conspiracy theorist Alex Jones and his media company, Infowars, from their platforms.

Jones has seized on the moment, selling his show Monday as a “world exclusive” responding to “being banned on the internet,” hashtagged #MondayMotivation as well as #Censorship.

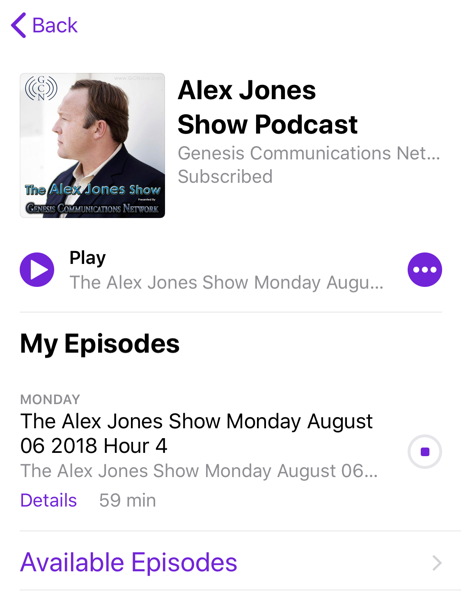

But if you went to Apple’s App Store, you could find his company’s app, which contains Jones’s podcasts and shows, and which has been “rocketing” up the App Store charts. Or, if you went to Facebook today and shared an Infowars link, it’d post. YouTube still hosts various Infowars associates such as Paul Joseph Watson, along with dozens of Jones’s appearances on other outlets.

And unlike in the case of the neo-Nazi publication The Daily Stormer, which was actually banned from the web by a variety of hosting and internet companies, anyone who wants to can go to Infowars.com and watch Jones sweat.

So if this is a ban, it’s an intentionally porous one. Facebook has explicitly argued for this sliding-scale strategy for responding to divisive users. “What we will do is we’ll say, okay, you have your page and if you’re not trying to organize harm against someone, or attacking someone, then you can put up that content on your page, even if people might disagree with it or find it offensive,” Mark Zuckerberg said in the weeks before the Infowars ban. “But that doesn’t mean that we have a responsibility to make it widely distributed in News Feed.”

In banning the Infowars page, Facebook took the next logical step in restricting access to Infowars content, but it still hasn’t outright banned the domain, and it has not disclosed how the News Feed algorithm is dealing with URLs from Infowars.com.

All of which is to say: There are many kinds of bans, and they each represent a different tool technology companies can use to police speech. Platforms can weaken the distribution of content they don’t like. They can ban the discovery of content they don’t like, as Apple has with Jones’s podcasts. Platforms can decline to host content they don’t like, as YouTube and Facebook have with InfoWars videos and pages, respectively. Or platforms can ban the presence of content they don’t like, regardless of where it is hosted or discovered.

These platforms sit atop the web in two different ways. One is that they enclose a piece of the internet, hosting the content; YouTube and Facebook Video are good examples of this. But in other circumstances, the platforms act as a skin over the top of the web. Apple’s podcast app is just a big directory of podcast feeds; Apple puts the hosting costs on podcasters. So to “ban” the Infowars podcast in this case is to remove the pointer to that feed from the app.

In Apple’s podcast app, all you have to do to keep listening to Jones is manually add the URL. It takes 10 seconds, and voila:

This overlapping set of bans and distribution slowdowns can be framed as incoherence on the part of the platforms, especially in Apple’s case: allowing an app with the same content it’s pulled from its directory of podcasts. While it cut Jones’s top-line distribution, it has also driven people to a more lucrative platform for Infowars. These moves can also be framed as underhanded, as in (unfounded) complaints about Facebook “shadow banning” conservative pundits by reducing their distribution within News Feed.

All these headaches are why the tech platforms historically have made the argument, as Twitter continues to, that these platforms are the embodiment of the “marketplace of ideas.” Facebook’s version is that it wants to “give everyone a voice.” It might not be pretty, an executive might grimace, but this is how the world works. Think about what this position gets the tech companies: They take no responsibility for which ideas, public figures, and publishers succeed, because those people “naturally” or “organically” rose to the top of their algorithmic systems.

Jones and his followers are probably right to be mad. They took the tech world at face value, played the game as it was sold to them by a generation of internet entrepreneurs, and they succeeded.

But the abstraction of the marketplace of ideas has always been embedded in a very particular set of technical operations. To be good on YouTube wasn’t just to make a good video, but to make good YouTube videos—that is, to optimize them to get distributed on the platform, so that your other videos would get served up, so that your channel would get recommended. Sure, some of the ideas were contained in the content people produced, but many of the ways to win in the marketplace were independent of anything inside the content. The key strategies were sociotechnical, based on an understanding of the platforms’ preferences and algorithmic signals.

The “internet” may have been a marketplace of ideas, but the way to gain the largest following was to understand the topology of social distribution, and the most important ideas were how the platforms thought of themselves.

As the “organic” functioning of these content systems has churned away, the big platforms have found some uncomfortable truths about what succeeded according to their extant rules. What they built is at odds with what they thought they were building. So, bit by bit, they are abandoning the abstractions of free speech, however that might be construed.

This is going to be an ugly, fraught process, but let’s be real: This is just the latest of many tweaks they’ve made to the structural conditions of the media. These same technology companies methodically disassembled the media industry in the course of less than a decade, snatching up most of the profits in digital advertising for themselves, and sending media companies careening down dead ends. Papers are struggling. Magazines are struggling. There are thousands fewer reporters than there used to be.

In the scheme of these things, it’s hard to get worked up over Jones’s right to be discovered in the Apple podcasts app. Many far-better journalists and pundits have been buried by the behavior of the platforms than this particular conspiracy theorist. But he and his fans have one thing right in their lamentations: These platforms have tremendous power, they have hardly begun to use it, and it’s not clear how anyone would stop them from doing so.