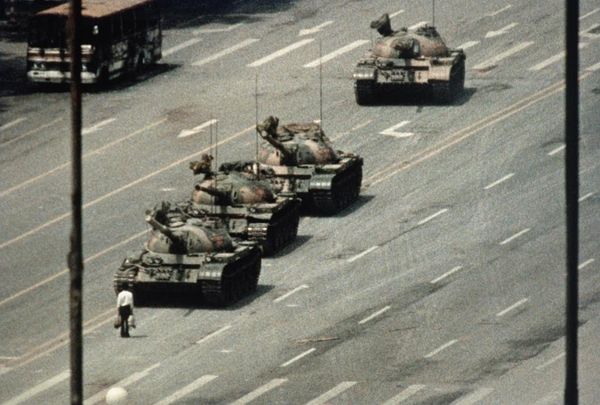

The brutal military crackdown on peaceful protesters in Beijing 30 years ago might have saved the Communist Party’s rule, but it has since become a cross to bear for the People’s Liberation Army.

Today, the world’s largest fighting force is still haunted by the Tiananmen Square tragedy in 1989, despite efforts to rebuild its image. After the bloodshed, it was the military that suggested the pro-democracy student movement be referred to not as a “counter-revolutionary rebellion” but as a time of “political turmoil”, two former PLA officers told the South China Morning Post.

They said the move to tone down the language around the crackdown reflected the anxiety and shame felt by many rank-and-file officers over a fateful decision that has tainted the military’s reputation and legacy.

Up to that point, the PLA had been widely respected by the Chinese public. Even during the turbulent decade of the Cultural Revolution from 1966, the military was largely uninvolved. Rather, it was instrumental in bringing an end to the chaos and setting China on the path of reform and opening up.

The crackdown in 1989 was unprecedented for the PLA and dealt a crippling blow to its reputation and morale – and the question over the legitimacy of the decision to send in the tanks and open fire on the protesters remains.

“[I believe] the Tiananmen crackdown will be revisited one day – it’s just a matter of time. The ultimate responsibility will fall to those military leaders who directly implemented the decision,” a retired researcher with the PLA’s Academy of Military Science, who requested anonymity, told the Post.

Throughout history and across cultures, following orders has been a fundamental principle of military service. But the absence of a written order on the mission from the commander in chief – late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping – puts its legality in doubt.

It is estimated that hundreds, or perhaps more than 1,000, civilians were killed during the crackdown that began on the night of June 3 and continued until the morning.

“No matter whether it is one or 10,000 people killed, it’s still wrong to shoot at unarmed civilians,” said a retired PLA officer who served in the army’s political department and also declined to be named. “But [the troops] had to do this dirty job because the party’s rule was in danger.”

According to the former military researcher, many commanders involved in the crackdown questioned the decision to use force to quell the protests, particularly since they had only been given a verbal order from above and never saw a written instruction from Deng, who was chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC).

This was further complicated by the fact that Zhao Ziyang, the party’s general secretary at the time, openly opposed a military crackdown. Without the support and approval of the party’s chief, the operation violated the long-held principle of “the party commanding the gun”.

Even then CMC vice-chairman Yang Shangkun and Xu Qinxian, commander of the 38th Army Corps that had been sent to Beijing, had qualms about carrying out the verbal order, according to the former researcher.

It is not known how many troops were sent in to crush the protests, but the number could be as high as 200,000, according to a book by US-based scholar Wu Renhua.

The retired PLA political officer said the instruction to commanders was to “clear out Tiananmen Square by June 4 – and whoever stands in our way is an enemy of the state”.

“Most officers and soldiers were only trained to use heavy weapons like machine guns and tanks. They didn’t even know there were things like rubber bullets, tear gas or other kinds of non-lethal weapons for crowd control,” said the former officer.

“To meet the deadline to clean up the square, some commanders asked their troops to shoot into the air to scare away the crowds – that was the only thing they could think of doing,” he said.

But although they started off firing into the air, ricocheting bullets hit many protesters as they fled and in the chaos and bloodshed, inexperienced troops panicked and started firing into the crowd, according to the former officer.

The army’s clean image was destroyed overnight, and in the minds of many, renmin zidibing – the army of our sons – became the feared and reviled tool of a killing regime.

It also left a psychological scar on the military, which is reflected in the effort to tone down the narrative around the crackdown.

The former researcher said the push to use “political turmoil” instead of the more provocative “counter-revolutionary rebellion” to describe the movement first appeared in a military academy reference book, the Chinese Military Encyclopaedia, in 1997. He said it was proposed by military advisers who believed it could help soften attitudes towards the crackdown.

Former president Jiang Zemin spoke of the “political turmoil” in 1989 during an interview with American journalist Mike Wallace in 2000, and the wording has since been widely used by state media.

Meanwhile, the suppression of the protesters also prompted calls for a separation of the army and the party, so the PLA would be a “national” force rather than a political one. But after a decade of debate, the idea was squashed by the top leadership in 2007, on the eve of the PLA’s 80th anniversary. It was labelled as a plot by hostile Western forces to topple communist rule in China and is now a taboo subject.

“But despite banning discussion of military nationalisation, the calls from within the PLA to rehabilitate the military and for a review of what happened with the student movement have never stopped,” the former PLA political officer said.

“Many senior military officers believe the students weren’t attempting to overthrow communist rule – they were just asking for a better political system. That’s why calling it a counter-revolutionary rebellion is wrong.”

On Sunday, days ahead of the 30th anniversary, Defence Minister General Wei Fenghe defended the Tiananmen crackdown, telling a regional defence forum that putting an end to the “political turbulence” had been the “correct policy”.

“Throughout the 30 years, China under the Communist Party has undergone many changes – do you think the government was wrong with the handling of June Fourth? There was a conclusion to that incident. The government was decisive in stopping the turbulence,” Wei said at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore.

But according to the former PLA researcher, military top brass involved in the crackdown still felt profound “guilt and shame” over the lives lost.

“None of those people in the PLA would feel a sense of honour for participating in the crackdown,” he said. “Instead they harbour a deep feeling of shame.”