When Cyril Ramaphosa stepped on to the balcony of Cape Town City Hall last Sunday, he closed a circle that had opened exactly 28 years earlier. It was a moment almost spiritual in its perfection, most especially in light of South Africa’s decline from rainbow nation to rotten republic.

On Sunday 11 February 1990, as the 37-year-old chairman of the Nelson Mandela reception committee, Ramaphosa stepped on to that balcony with the icon of the struggle against apartheid; a few hours earlier he had accompanied Mandela as he walked out of prison after 27 years.

Standing on Mandela’s left, Ramaphosa held the microphone as the 71-year-old future president spoke to tens of thousands of people on the Grand Parade below him. “Friends, comrades and fellow South Africans, I greet you all in the name of peace, democracy and freedom for all,” said Mandela.

“I stand here before you not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people. Your tireless and heroic sacrifices have made it possible for me to be here today. I therefore place the remaining years of my life in your hands.”

On Sunday 11 February 2018, Ramaphosa’s job as the 65-year-old recently elected leader of the African National Congress (ANC) was to launch the Mandela centennial celebrations. But the crowd’s biggest cheer was reserved for his announcement that in his negotiations for the removal of Jacob Zuma as president of South Africa, he was doing as Mandela did: putting the people first.

“We should draw deep into Madiba’s wisdom, we should draw deep into Madiba’s style of doing things in an orderly manner, in a purposeful manner, in a way where we focus,” he said, standing in front of a large photograph of Mandela’s smiling face.

The fates could hardly have delivered a better platform for Ramaphosa to announce himself as the soon-to-be fifth president of democratic South Africa. And as he settles into the office Mandela once occupied at the Union Buildings in Pretoria it will not be hard to imagine the “old man”, as we was affectionately known, flashing that wide and infectious grin, maybe even doing the “Madiba jive”. Finally, the man he saw as his natural successor gets the chance to rule.

South African politics is the gift that keeps on giving for movie-makers. Parts of Nelson Mandela’s story have already made it to screens large and small, the great man played by stars including Morgan Freeman, Danny Glover, Sidney Poitier, Idris Elba, Laurence Fishburne and Terrence Howard.

The life of Jacob Zuma offers darker material – something like House of Cards on steroids. The screenplay of this horror film would feature Zuma’s rumoured role as a torturer – and worse – in exile in Mozambique, unlikely amounts of sex (Zuma has had six weddings, and 22 children with 11 women), a rape trial, episodes of untold riches illicitly gained and foolishly lost, vignettes pointing to devilish cunning in the quest for unbridled power … and a cast of baddies even Hollywood will struggle to populate. The final scene, many South Africans hope, will be set in a prison cell.

As for Ramaphosa, this movie will be aimed at the art-house circuit. At the heart of the cerebral, unhurried script will be an engaging, softly spoken man – much like Mandela – who became involved in student politics while studying law.

It will relate how he launched the National Union of Mineworkers then the Congress of South African Trade Unions, took over as secretary-general of the ANC in 1991 and spent years at Mandela’s right hand. Much of the action will take place around the negotiation table – formulating South Africa’s post-democratic constitution, crafting the National Development Plan supposed to transform the country by 2030 but largely ignored by Zuma, and finalising the “Zexit” deal that hands him the reins of power.

It will also involve elections: the ANC leadership fight in 1997 that he lost to Thabo Mbeki, sending him off into a business career that gave him an estimated fortune of $450 million (£325 million); the poll for ANC deputy president in 2012 in which he amassed even more votes than the victorious candidate for the party leadership, Zuma; the contest with Zuma’s ex-wife, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, in December 2017, which handed “CR17” the ANC’s top job; and the general election next year, by which time he hopes to have done enough to reverse a decline in ANC fortunes, which has left the outcome in doubt for the first time since 1994.

South Africa is not relentlessly opinion-polled, so there are no facts or statistics upon which to base a prediction about whether this is something he can pull off. But sentiment since Ramaphosa’s victory at the ANC elective conference in Johannesburg on December 18 has clearly changed. The rand, for example, has strengthened by 2.7 per cent against the pound (and by 12.7 per cent since its 2017 low on November 10). Delegates to the World Economic Forum, jaded by years of Zuma’s economic recklessness, returned in numbers to South Africa’s room in Davos last month, eager to shake the hand of a beaming, avuncular Ramaphosa.

While expressing frustration at the speed of the transition at the Union Buildings, commentators who have long since exhausted their adjectival lexicon in scathing assessments of the ANC’s reluctance to deal with Zuma have started to see chinks of light. Writing in the Sunday Times in South Africa at the weekend, financial journalism doyen Peter Bruce – once UK news editor of the Financial Times – even went as far as advising Ramaphosa how to win next year’s election.

The main editorial in the same newspaper – a title which has been at the forefront of exposing Zuma’s corrupt activities – said: “Ramaphosa is drawing on a deep reservoir of goodwill from South Africans across the board … but only bold steps will allow South Africa to fully capitalise on the hope that {his} election has engendered in an exhausted nation.”

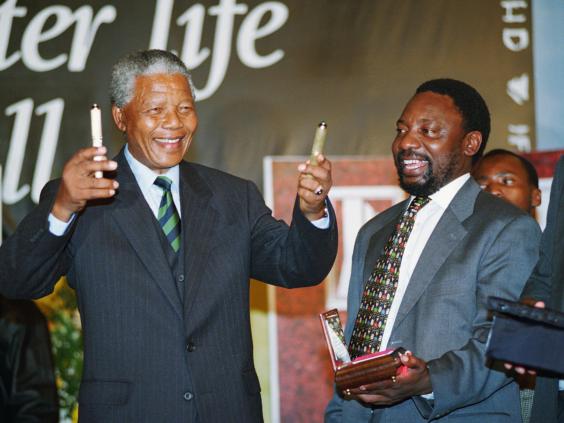

The key thing to understand about Ramaphosa is that people remember him walking out of prison with Mandela; leading the ANC team negotiating the end of apartheid with the National Party government; handing a bound copy of the new constitution to Mandela in 1996. As a result, he is almost universally trusted. Marikana misstep aside (see above), workers remember him as someone who led a three-month miners’ strike in 1987. Business has seen him prosper. Even rival politicians respect him, a refreshing change after years of parliamentary violence whenever Zuma showed his face.

The day after Ramaphosa’s election as ANC leader, former apartheid defence minister Roelf Meyer said: “If there is one man today in South Africa that can help us put the pieces together‚ it is him. That is why South Africans are feeling much better this morning than yesterday morning.”

Meyer, who grew close to Ramaphosa during constitutional negotiations in the 1990s, said he had never experienced him as greedy for power. “He has based his skills on the fact that he has respect and understanding for the constitution.”

Even FW de Klerk, the National Party president who freed Mandela, respects Ramaphosa, telling biographer Ray Hartley: “His relaxed manner and convivial expression were contradicted by coldly calculating eyes, which seemed to be searching continuously for the softest spot in the defences of his opponents. His silver tongue and honeyed phrases lulled potential victims while his arguments relentlessly tightened around them.”

In the same way that Donald Trump’s successor as US president will have a honeymoon period based on nothing other than the fact that s/he isn’t Trump, Ramaphosa can expect a few months in which criticism will be muted, constructive engagement the order of the day.

It’s just as well, because his agenda is long and difficult if he is to form a new ANC government in 2019. First, he will have to mount a series of precision raids on the den of thieves Zuma built around himself. Only a purge of epic proportions, followed by prosecutions and prison sentences, will satisfy South Africans who have become numbed to the “state capture” perpetrated by those dubbed the “president’s keepers” in a recent best-seller.

Then he will have to rebuild destroyed ministries and institutions, and we can only hope the hundreds of good men and women cast aside in the Zuma years will be prepared to return to their posts – most critically at the South African Revenue Service. The tax collector was the brightest star in the government’s firmament until Zuma eviscerated it and must be revitalised if the massive and vital welfare state is to survive.

As for re-establishing the ANC as a movement with the interests of the people at its heart, Ramaphosa’s best hope is Mandela’s centennial. By accentuating his links with “the father of the nation”, by talking about the values Mandela espoused, he can begin to erase the memories of the Zuma years. And if he can do that, maybe he can even revive hopes that South Africa can buck the lamentable post-colonial African trend of being run by “big men”.

It’s a tall order, but Ramaphosa appears motivated, energised, determined and healthy. The stars have aligned for him, and the will for him to succeed is almost tangible.

A statue of Mandela will be placed on the Cape Town City Hall balcony later this year. One day, maybe Ramaphosa will get his own alongside it.

Dave Chambers is Cape Town bureau chief of South Africa's Sunday Times and timeslive.co.za