NO CONFLICT since the 1940s has been bloodier, yet few have been more completely ignored. Estimates of the death toll in Congo between 1998 and 2003 range from roughly 1m to more than 5m—no one counted the corpses. Taking the midpoint, the cost in lives was higher than that in Syria, Iraq, Vietnam or Korea. Yet scarcely any outsider has a clue what the fighting was about or who was killing whom. Which is a tragedy, because the great war at the heart of Africa might be about to start again.

The cause of the carnage

To understand the original war, consider this outrageously oversimplified analogy. Imagine a giant house whose timbers are rotten. That was the Congolese state under Mobutu Sese Seko, the kleptocratic tyrant who ruled from 1965 to 1997. Next, imagine a cannonball that brings the house crashing down. That cannonball was fired from Rwanda, Congo’s tiny, turbulent neighbour. Now imagine that every local gang of armed criminals comes rushing in to steal the family jewels, and the looting turns violent. Finally, imagine that you are a young, unarmed woman who lives alone in the shattered house. It is not a pleasant thought, is it?

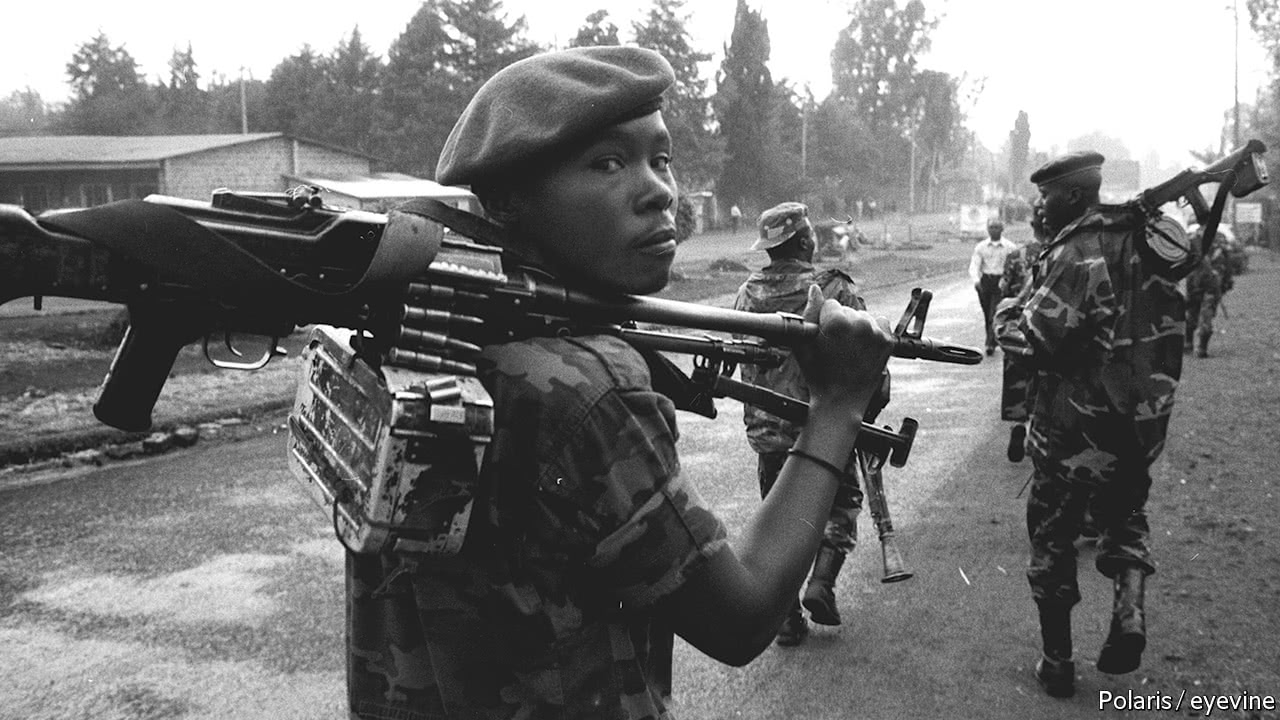

Mobutu and his underlings looted the Congolese state until it could barely stand. When a shock struck, it collapsed. The shock was the Rwandan genocide of 1994. The perpetrators of that abomination, defeated at home, fled into Congo. Rwanda invaded Congo to eliminate them. Meeting almost no resistance, since no one wanted to die for Mobutu, the highly disciplined Rwandans overthrew him and replaced him with their local ally, Laurent Kabila. Then Kabila switched sides and armed the génocidaires, so Rwanda tried to overthrow him, too. Angola and Zimbabwe saved him. The war degenerated into a bloody tussle for plunder. Eight foreign countries became embroiled, along with dozens of local militias. Congo’s mineral wealth fuelled the mayhem, as men with guns grabbed diamond, gold and coltan mines. Warlords stoked ethnic divisions, urging young men to take up arms to defend their tribe—and rob the one next door—because the state could not protect anyone. Rape spread like a forest fire.

The war ended eventually when all sides were exhausted, and under pressure from donors on the governments involved. The world’s biggest force of UN blue helmets arrived. Kabila’s son, Joseph, has been president since his father was shot in 2001. He has failed to build a state that does not prey on its people. Bigwigs still embezzle; soldiers mug peasants; public services barely exist. The law counts for little. When a judge recently refused to rule against an opposition leader, thugs broke into his home and raped his wife and daughter.

Mr Kabila was elected for a final five-year term in 2011. His mandate ran out in 2016, but he clings to the throne. He is pathetically unpopular—no more than 10% of Congolese back him. His authority is fading. He can still scatter protests in the capital, Kinshasa, with tear gas and live bullets. And few Congolese can afford to take a whole day off to protest, in any case. But in the rest of this vast country, he is losing control (see Briefing). Ten of 26 provinces are suffering armed conflict. Dozens of militias are once again spilling blood. Some 2m Congolese fled their homes last year, bringing the total still displaced to around 4.3m. The state is tottering, the president is illegitimate, ethnic militias are proliferating and one of the world’s richest supplies of minerals is available to loot. There is ample evidence that countries which have suffered a recent civil war are more likely to suffer another. In Congo the slide back to carnage has already begun.

Beyond Africa, why should the world care? Congo is far away and has no discernible effect on global stockmarkets. Besides, its woes seem too complex and intractable for outsiders to fix. It has long had predatory rulers, from the slave-dealing pre-colonial kings of Kongo to the Kabila family. Intrusive outsiders have often made matters worse, from the rapacious Belgian King Leopold II in the 19th century to the American cold warriors who propped up Mobutu for being anti-Soviet.

Nonetheless, the world should care and it can help. Congo matters mainly because its people are people, and deserve better. It also matters because it is huge—two-thirds the size of India—and when it burns, the flames spread. Violence has raged back and forth across its borders with Rwanda, Uganda, Angola, South Sudan and the Central African Republic. Studies find that civil wars cause grave economic harm to neighbouring states, which in Congo’s case are home to 200m people. Put another way, if Congo were peaceful and functional, it could be the crossroads of an entire continent, and power every country south of it with dams on its mighty river.

If outsiders engage now, the slide back to war may yet be held in check. First, cuts to the UN peacekeepers’ budget, made partly at President Donald Trump’s behest, should be reversed. The blue helmets are not perfect, and cannot protect remote villages. But they can protect cities and are the only force that Congolese trust not to slaughter and pillage. Second, Mr Trump’s welcome sanctions against Mr Kabila’s moneymen—building on earlier embargoes on conflict minerals—should be extended. Donors should press Mr Kabila to keep his promise to hold elections by the end of the year, and not to flout the constitution by running again. In this, they should make common cause with sensible African leaders. The Congolese opposition should take part in the vote, instead of boycotting it.

A flicker of hope

The omens are not all bad. South Africa has just dumped Jacob Zuma (see article), who indulged Mr Kabila’s claim that Western pleas to uphold Congolese law were imperialism. (Mr Zuma’s nephew reportedly has oil interests in Congo.) Cyril Ramaphosa, Mr Zuma’s successor, is honest and pragmatic. Just as Nelson Mandela was repelled by Mobutu, and hastened his departure, so Mr Ramaphosa is surely repelled by Mr Kabila. He has experience negotiating the end of bad things, including apartheid, Northern Ireland’s troubles and Mr Zuma’s presidency. He must not let Congo go back to hell.