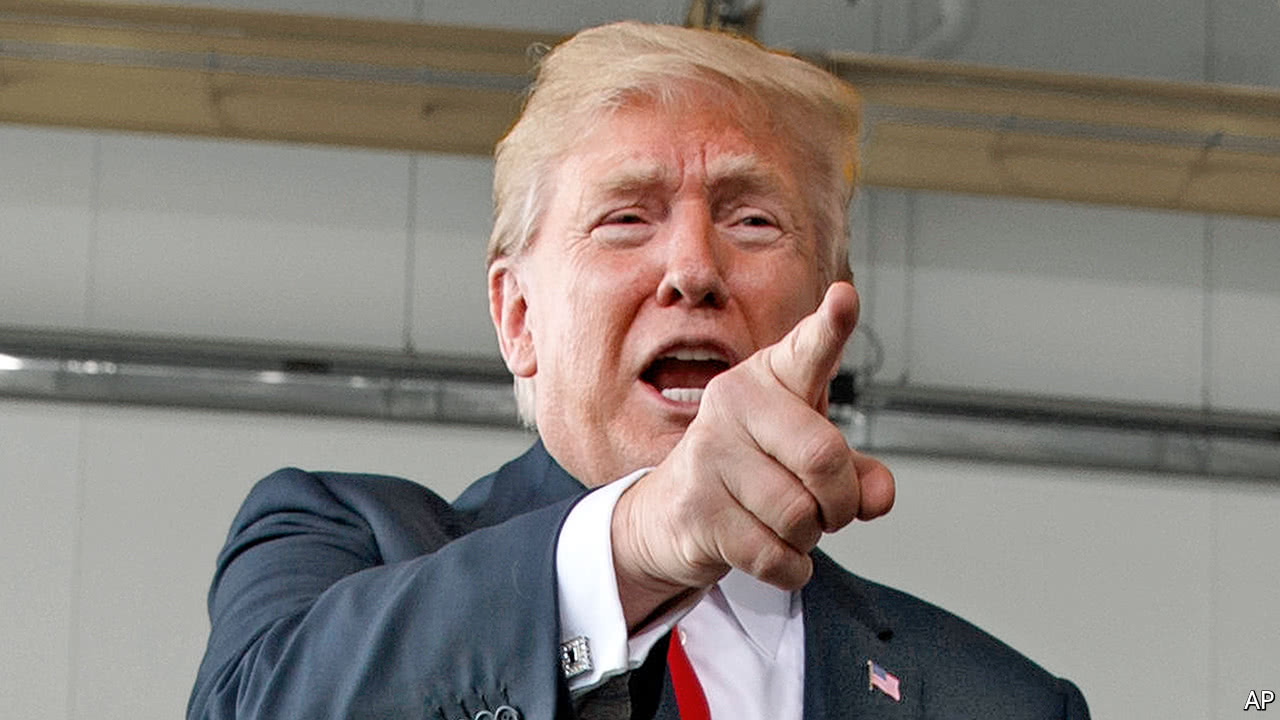

EVEN by the reality-TV standards of this White House, the manner in which Rex Tillerson was sacked as secretary of state was jaw-dropping. President Donald Trump fired him by tweet, saying that he would be replaced by Mike Pompeo, director of the CIA. He did not call him until much later, nor did he offer an explanation. Mr Tillerson’s spokesman said that he had no idea why his boss had been fired. So he was fired, too.

Mr Tillerson was a poor secretary of state. Having run ExxonMobil, the tenth-biggest company in the world by revenue, he treated diplomacy like business and his department like a division ripe for restructuring. He seemed to regard his underlings as idle assets and they repaid him with their scorn (see article). So, too, did the president, at least after reports that Mr Tillerson had called him a “moron”.

The new man, Mr Pompeo, has distinguished himself in Mr Trump’s eyes by talking up a Trumpian, America First view of the world (see Lexington). The result may well be a more co-ordinated policy, with fewer public rifts between the State Department and the White House. But when you look at the two biggest tests facing American foreign policy, the new set-up does not inspire confidence.

The first of these is North Korea. Mr Trump’s decision to kick-start negotiations by talking directly to Kim Jong Un is unconventional. A photo-op with the American president is a great prize for Mr Kim and, rather than holding it out as a reward, Mr Trump has chosen to give it away cheap. That is not necessarily a bad idea, given that other approaches have failed and that merely talking is a chance for him to reinforce deterrence by setting out his red lines.

The trouble is that, whereas the talks aimed at ridding the Korean peninsula of nuclear weapons will be delicate, complicated and technical, Mr Trump is impulsive and self-indulgent—as this week’s sacking of Mr Tillerson showed. Mastering the specifications of the North’s programme and knowing how to blunt it require deep expertise. Any deal to ensure that the North does not cheat, as it has so often before, will need to be thorough and enduring. America must not enhance its own security at the cost of lower security for its allies in South Korea and Japan. And if the talks should come to nothing, as is likely, both sides will need to be sure that the bad blood does not lead to conflict.

The combination, to put it mildly, sits ill with Mr Trump’s style of government. In a properly run administration, the fiddly stuff could be left to underlings. Yet America has no ambassador to South Korea and no under-secretary for arms control. Even if it did, it is not clear that Mr Trump would give them the time of day. He shows every sign of thinking that he has the flair to broker a breakthrough all by himself. There is a risk Mr Pompeo would seek to flatter his boss by agreeing.

By a curious symmetry, the second test of American policy involves a nuclear deal that Mr Trump seems determined to wreck. In May he is due to decide whether to stick with the agreement that curbs Iran’s nuclear programme or pull out. Mr Pompeo, unlike Mr Tillerson, is a longtime opponent, as are many Republicans. A pull-out is therefore likely.

That would be a mistake. When it comes to deals, Mr Trump always believes that he can get a better one—especially if they were negotiated by his predecessor, Barack Obama. But the Iran deal is already the result of hard-fought trade-offs. The chances that it can be substantially renegotiated are slim indeed. Opening it up in the hope that America can expand it to force Iran to limit its regional ambitions is almost certain to fail.

If America walks away, its European allies will stick with the deal but they will conclude that Mr Trump puts a low value on the transatlantic alliance. The nuclear agreement may not collapse immediately, but the odds would increase of a nuclear arms-race in the Middle East, as Saudi Arabia and Egypt began to prepare for the day when Iran had the bomb. And because of the symmetry, Mr Kim would surely be less willing to think he could trust an agreement struck with Mr Trump.

It’s simple really

To hope that H.R. McMaster, the national-security adviser, who may shortly be fired himself, or James Mattis, the defence secretary, can be relied on to constrain the president is to clutch at straws. Mr Trump does not have a foreign policy so much as a worldview rooted in grievance and a belief that others must lose for America to win. He has his tariffs, his talks with North Korea and maybe soon a Middle East peace plan. The world is about to witness Trump unbound. What could go wrong?