I like to think of myself as a strong swimmer. I’m not fast, I can’t dive or tumble turn, but when I get a lane to myself I’ll happily bash out 50 or 60 lengths. Give me a nice big lake, and my idea of heaven is to backstroke into the middle and watch the swallows overhead. I don’t worry that I’ll cramp up or suddenly forget how to float.

But I’ve never fancied water polo. If you’ve not watched it, it’s a sort of cross between swimming, basketball and wrestling, usually played in a pool that’s so deep you have to tread water or drown. There are two teams, two goals, a large ball and an ungodly amount of throwing, catching and flat-out sprinting. Aquatics GB, the governing body, says players can swim two miles in a single game, and need “remarkable stamina” to cope with all the holding and pushing.

The what? Oh yes: this is very much a contact sport. Except for the goalies, players can only use one hand to catch or throw the ball – but the other gets up to all sorts of mischief, from fending off opponents to dunking them underwater. There’s a lot of whistleblowing and fouls and occasional sending-offs for “brutality”. In a Q&A to explain the frankly impenetrable rules, the Carolina Water Polo club actually asks: “Why is the ref condoning the drowning of my child?”

As an active 60-year-old, I don’t like to think of anything as a young person’s game – but if I did, this would be it.

And yet here I am, on a Sunday afternoon in south-west London, about to jump in the pool and terrified I’ll let down both my teammates and myself. It’s all John Starbrook’s fault.

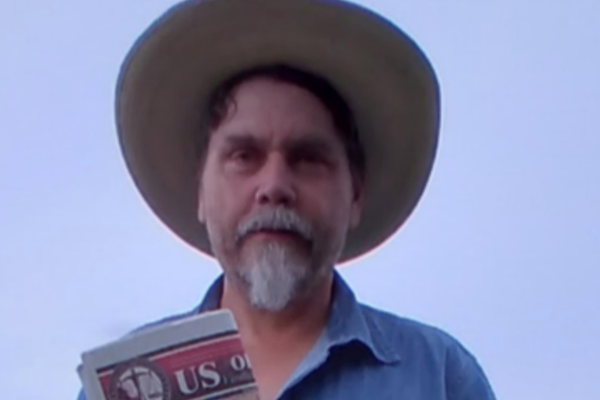

At 93, Starbrook is definitely the oldest water polo player at Hampton Pool (which welcomes any swimmer aged eight or over), and probably the oldest in the country. Alan Cammidge, the retired police officer who is about to referee our game, describes him as “a remarkable athlete. He has all the skills in the book and regularly scores.”

Starbrook has been a keen swimmer for almost 80 years, ever since he left school at the end of the second world war. As a young man, he raced butterfly at the national swimming championships. He didn’t win anything in his saggy woollen costume, but he had a lot of fun and never lost his love of the water. When he turned 80, he celebrated by swimming a mile or so across the Gulf of Corryvreckan, between the Scottish islands of Jura and Scarba. He still swims three times a week.

A couple of weeks ago, when I wrote about wanting to live to 100, a reader asked: “Why the hell would you wanna reach 100? It’s all downhill after 40.” All I can say is, that person has never met John Starbrook.

Everyone who has seems to love “the Legend”, from the kids in Hampton to his fellow members of the Thames Club, a sports centre near his home in Staines, Middlesex. And if his nickname sounds a little over the top, that’s because you don’t know everything else he gets up to. When he’s not with Judy, his wife of 62 years, he spends most mornings at the gym. “The spin classes get me moving,” he says, as we chat in the cafe. “And then, about 4pm or 5pm, I go back to work on my upper body.”

This is him taking it easy. After taking up running at the age of 53, Starbrook has done a total of 52 marathons, everywhere from London to Denmark to Barbados. His fastest time was 4 hours 14 minutes, in Snowdonia 20 or 25 years ago. He likes to joke that it was because he was being chased by sheep. His most recent – and probably final – 26-miler was in 2019, when he was 88. He has also done a couple of parachute jumps and a bunch of triathlons, though he has been known to struggle with the costume changes. “The first one I did, it took me seven minutes to get my wetsuit off. My mates were all standing around and barracking me.”

In the process, he has raised over £50,000, mostly for Age UK. The charity, which runs a lot of local exercise classes, calls him its ambassador, for his ability to inspire older people and challenge stereotypes about them. “A lot of people seem to think that when they hit 50, they’re old,” he has said. “I hear that and I don’t know what they’re talking about.”

His granddaughter Yarna shared his enthusiasm enough to run the London Marathon alongside him, but he never quite convinced his son. When Starbrook was still pounding the pavements, his boy would ask him why he bothered. Couldn’t he just take a bus?

He’s not the only sceptic. “About 10 or 15 years ago,” Starbrook remembers, “the doctor said, ‘You’ve got to pack in that running.’ I said, ‘Yeah, all right’ – and I did about 15 marathons after that.”

Then he breaks off to chat with one of the many women who can’t resist saying hello on their way to class. “His harem,” another regular calls them.

“How do you think you’ve kept in such great shape?” I eventually manage to ask.

“I don’t do anything special,” he says, “though I’ve never smoked and never drank much. My diet’s pretty normal. I have porridge in the morning and I eat a lot of veg, and not much fried food. I think it’s just my genes.”

If so, it’s probably on his mum’s side. He lost his dad, Samuel, when he was five months old – to pneumonia, he thinks, though his mum never liked to talk about it. It was the 1930s, there was no money and Emily struggled to raise him, so Starbrook, the youngest of the three kids, spent 14 years in a children’s home. “It was all right,” he says. “I didn’t know any different. You don’t when you’re young.”

Emily remarried, had another son and daughter and lived to 86. Starbrook’s younger brother, David, got into judo and won silver and bronze at the 1972 and 1976 Olympics. Now 78, he still coaches the sport.

Starbrook dates his own fitness back to his first job, as a 15-year-old, with United Dairies in his home town of Croydon. In 1945, of course, everyone had milk delivered to their homes. United’s milk floats were mostly driven by old men, as everyone of fighting age was in uniform; they would stay with their horses (yes, horses) while youngsters like Starbrook ran the pints to customers’ doors. “I’m sure that was what made me fit,” he says. Starbrook’s driver would occasionally carry a bottle all the way to the doorstep, but only if he knew there was a cup of tea waiting for him.

When the time came for national service, Starbrook ended up in the army medical corps – and again fate lent a hand. His superiors were obsessed with swimming, “so anyone who was a swimmer was made. I didn’t do any soldiering – all I did was take part in army competitions.”

It’s now 28 years since he retired, after raising three children, helping to build power stations, working in various shops, and a whole quarter-century of delivering eggs to businesses around Heathrow. “A lot of people still know me as John the Egg,” he says, “although I’ve been retired for all these years.”

Did he think he would still be going strong at 93?

“I thought I’d go on until about 70. When I was younger, I thought, ‘I wonder if I’ll still be alive in the year 2000.’ That was in 1945. I won’t make it to 3000, anyway.”

How long does he reckon he has left? Is that an awful question? We all think about it, don’t we?

“People say, ‘Oh, you’ll go on to 100!’ But I don’t care how long I go on for, as long as I’m not in any pain.”

And, barring the odd twinge, he isn’t. He has a touch of arthritis in one knee, which occasionally keeps him out of his spin class. He also takes a blood thinner because of an irregular heartbeat – but, as he says: “Being the age I am, I’m lucky that’s all I’ve got.”

A few days after our chat, I join him for that game of water polo. In a fast and furious 40 minutes, I touch the ball just twice, even though this pool has a shallow end, so I can actually stand up in places. That may be just as well, since I keep forgetting which side I’m on. Starbrook is with the whites, while I’m with the blues, but the only way you can tell is by the caps we wear to protect our ears – and since mine is on my head I can’t see it.

I still have a great time. After a few minutes I find myself racing towards the ball, though I have no idea what I’d do with it. And when it comes arcing towards our goal, I desperately flail up an arm in an attempt to deflect it. I think I’m more of a liability than an asset for the blues – getting in everyone’s way, blocking the goalie’s view – but no one is cruel enough to say so, and I get a real buzz from my pointless exertions.

“You survived and should be very proud of yourself,” Cammidge tells me afterwards. I think he’s being kind, but I’ll take it.

Starbrook’s ever-smiling presence has a lot to do with it. “I’m never bothered about anything,” he had told me earlier. “My missus says I’m on my own cloud.” The Goal Hanger, as he is sometimes known, is not racing around like the rest of us, preferring to dog the opponents’ goalie, waiting for a chance to bang the ball into the net – but he’s happy to be in the thick of things, and not averse to a bit of rough-and-tumble. The week before he had pushed one of the blues underwater, smiling all the while. “He can still get up and down the pool when he needs to,” Cammidge says. “And do not underestimate his drive and commitment in the tackle.” It looks like I got off lightly.

As we change after the game, another player asks me if I enjoyed myself. Will I be back? I barely have to think about it. Yes, I did, I say. And yes, I will.

To support Age UK or find out more about its work, go to ageuk.org.uk